I’m proud to be a player in Alex Augunas’ Starfinder campaign: Teenaged Wasteland (which you can read about right here on Know Direction). It’s quickly become my favorite ongoing game, and in the process has made me take a closer look at the very nature of a campaign. I highly encourage everyone looking to run their own home game to take some time to read his articles on planning, developing player engagement, and using Discord to organize data and encourage roleplaying. But this post isn’t just bringing attention to Alex’s practical articles. On the contrary, I’d like to focus on something a little more abstract:

Your Campaign is a Business

This metaphor feels so heavy-handed that I’m tempted to just end the article here, but first I have to clear up some misconceptions. Your initial instinct might be to see the GM as the owner-manager and the players as the customers. There’s nothing wrong with that relationship, but it’s not the only one. There are as many ways to run campaigns as there are ways to run businesses, and if you learn anything from this article it should be: The relationship you have with your fellow players and the amount of time and energy you can invest in the game is the only two things that really matter when deciding how to organize a campaign!

So what’s the point? Using a business model to help organize your campaign is not about making permanent resolutions. Rather, it allows you to contextualize logistics decisions in a way that makes it easy to test new methods of campaign management while minimizing the risk of permanent damage to your game. Just like businesses need to adapt to survive shifts in the market, campaigns will often find themselves having to adapt to both shifting player interests and real-world circumstances. While it can be tempting to just shutter a campaign with minimal player interest and start something new, in my experience being able to rekindle that shared nostalgia and reorganize the campaign will deliver a more satisfying game.

Players & Gamemasters: from Recipients to Co-Owners

Players as Recipients — A charity is an organization that raises money from donors to help recipients. Both the charity and recipients have very little input on the product, but this is not a strictly inferior business model. The GM and PCs having less input minimizes pressure as both the product and guidelines are developed and managed by a third-party. This model also opens up unique organization platforms, up to and including huge multi-table specials at conventions! This is also the ideal model for playtesting published adventures.

Example — Your favorite Organized Play has an awesome sea devil-themed adventure you want to run using their guidelines.

Players as Consumers — Many GMs plan their campaigns before they even know who is playing. There are advantages to this approach, especially if you want to minimize potentially alienating some of your players with perceived bias. This relationship can be useful for GMs who don’t know the preferences of their current group. This method can also be ideal for managing a sandbox-style living world that prioritizes verisimilitude over individual character’s stories.

Example — You have made the aforementioned sea devil adventure your own, adding in custom encounters.

Players as Guests — Guests are provided an ongoing service instead of a finished product. Like an architect designing a hotel, the campaign itself is still developed independent of the players, but the GM can adjust details of the game as it progresses to suit their player’s tastes. It often serves as a bridge between models, especially if you want to transition between published and home games.

Example – You have further adjusted the aforementioned sea devil adventure to suit your friends.

Players as Investors — A patron is someone who funds a project with minimal interference. In this style of campaign, the players give the GM some initial input, but then step back and let the GM take full control. This most often takes the form of character biographies, which can then be used by the GM to exploit a character’s weaknesses draw in an invested player. If a player loses interest in their initial investment, the campaign is likely to treat the player as a guest instead. And if a player’s investment accrues more interest over time, an investor can easily become a shareholder instead.

Example — Your friends want to play as sea devils! You know of a great sea devil adventure and want to use it as a starting point for your amazing sahuagin adventure!

Players as Shareholders — Shareholders play an active and ongoing role in the development and progress of a campaign. This will often develop out of a “players as investors” model. This does not mean that players have full control of the campaign, but rather that the GM actively seeks their player’s preferences and gives them more free reign over the setting. While some groups might find it inorganic, others appreciate using this model to explore themes that involve more than a single character. This model helps facilitate between-session roleplay without a GM having to micro-manage each session.

Example — You’ve decided to take a survey and it turns out your players want less aquatic combat encounters, but still want to play as sea devils. Let the coastal raids begin!

Players as Managers — Managers are not owners, but rather a person responsible for administering a division within a company. Many groups can thrive when players help run a campaign. Now, this can range from players tracking initiative to outright deciding what kind of adventure the party is going on next. A manager doesn’t just fill out an occasional survey, they outright tell the GM what they want to do. This is an exciting prospect for both GMs who love to adlib and those who enjoy sandbox games with a less cohesive story. This is also a common model with leadership and mercantile campaigns where players have to manage extensive subsystems that the GM might not have the time or energy to manage themselves.

Example — Your sea devil party wants to take over the world! One friend is going to help use various sourcebooks to help map out the oceans and coasts. Another wants to use a troop management system they found from an awesome third-party publisher. They’ll make some Recall Knowledge checks and use what information they have to decide where to invade first!

Players as Co-Owners — Oftentimes groups will take turns GMing the same campaign. While this can shift a story’s focus, it can help prevent one GM from experiencing complete burnout. It can help if one player is the defacto GM for the primary story, allowing players to interweave their character’s own substories in with the main plot. It makes it hard to interweave certain secrets into the campaign, but different players can frequently collaborate to try to surprise the rest of the group.

Example — One of your players wants to run the other sea devils through a raid of Sandpoint. They invite you to play your favorite NPC as your PC and you revel at the chance to exact sharky justice in the name of Kelizandri.

Session Organization: From One-Shots to Franchises

Campaigns as Pop-up Shops — Some adventures aren’t intended to be long-running campaigns. This model thrives when everyone playing understands from the outset that this is a one-shot deal. It gives players the opportunity to use radical character concepts and GMs the opportunity to test dangerous encounter ideas. There is a possibility that a pop-up shop might stick around and become a long-running campaign, but if you try focusing too much on that as a goal you’ll lose sight of what makes this model successful.

Example — You want to run an adventure you found where PCs fight off an invading force of Sea Devils. That’ll be a great chance to playtest those new classes from Secrets of Pastries!

Campaigns as Outlets — In manga there is a term called “omake”. These comics are essentially non-canonical “bonus comics” intended to give the audience some extra content often structured as bloopers, outtakes, and “what if” scenarios. Campaigns can use the same characters and/or setting to introduce radical new ideas and themes without disrupting the “primary campaign” by using the outlet model. They can even be done semi-canon, often involving elements like traveling to the plane of dreams, or being abducted by the fey. This category is very popular when using the “Players as Co-Owners” model. It can also apply to groups who enjoy playing short campaigns inspired by or parodying pop culture.

Example — What if our Rise of the Runelords PCs took a day to relax at the beach when the Sea Devils attacked?

Campaigns as Specialty Stores — Campaigns using the specialty store model focus on one specific theme and story. This model is very common with campaigns based on existing IP. It also works great when faced with player fluctuation, as it’s much easier to get returning players caught up. A specialty store campaign often uses a pretty formulaic approach, with parties taking on the same jobs from the same base of operations while a grander scheme unfolds from the same antagonistic force.

Example — This campaign will be focused on playing sea devils invading different coastal cities around Golarion.

Campaigns as General Stores — The general store model is ideal for classic campaigns that don’t want the confines of a specialty store but want to reign things in more than a department store. I see this as a sort of default or “middle-ground” campaign, and most of you have probably played in or run a campaign like this. The general store model likely has an ongoing story, but is probably sub-divided into dungeon adventures that let the GM explore a variety of classic staples for their genre. They are going to have some restrictions on character choice, often only “banning” certain unthematic options. These campaigns tend to shy away from complex subsystems that will only be used once or twice, such as investigations and verbal duels.

Example — This campaign will start off defending Sandpoint from Sea Devils, but from there the adventurers will begin to travel across Varisia. Also one of the PCs wanted to be a sea devil, but they agreed to instead play a malenti, a type of mutant sea devil that looks like an elf.

Campaigns as Department Stores — A department store has anything and everything, both in terms of mechanical options and narrative freedom. This versatility means it has the potential to run for a long time, often with multiple casts of characters coming into the same world in waves. These campaigns are more open to sudden thematic shifts than a general store and tend to use more diverse sources of rules than any other, employing more subsystems and uncommon options. These campaigns tend to be run by and for those who enjoy throwing different ideas at the wall to see what sticks. These work great for kitchen-sink campaigns that want to use as much material as possible.

Example — After traveling across Varisia, your sea devil-slaying heroes wind up in Numeria and have to get a number of technological augmentations to offset those limbs they lost fighting a particularly sharkshasa who has come from a far off world to invade Golarion!

Campaigns as Chains — The chain business model prioritizes consistency across multiple venues. A campaign using this model is one that can be picked up by multiple groups but retains the same core elements regardless of who is running it. These groups do not exist completely independent of one another, but rather as a part of an ongoing campaign that can theoretically go on for years. The advantage of this system is that even if a group falls apart, you can continue playing the same campaign even if you have moved halfway across the world.

Example — Pathfinder Society has a great scenario about battling sea devils, and you can always find players who want to play it at local or online conventions.

Campaigns as Franchises — The difference between a franchise and a chain is ownership. A franchise happens when a campaign evolves beyond the control of a single person or group. This is most common when a campaign becomes a published setting. It can happen organically within a group when the canon, roleplay, and games played within and as part of the campaign go beyond the GM’s control, becoming a multi-campaign franchise. It is extraordinarily difficult to get a franchise to stick, but it’s not hard to find games like as publishers like setting their work in an established setting.

Example — After live-streaming your sea devil campaign for a year you’ve decided to write up a campaign guide so other people can enjoy all the sharky goodness. You’ve started to stumble on sea devil fanart clearly set in your continuity, and now people are asking about a conspiracy theory regarding the sahuagin queen in an AmA and you were certain you never actually gave the queen a name…

In Conclusion

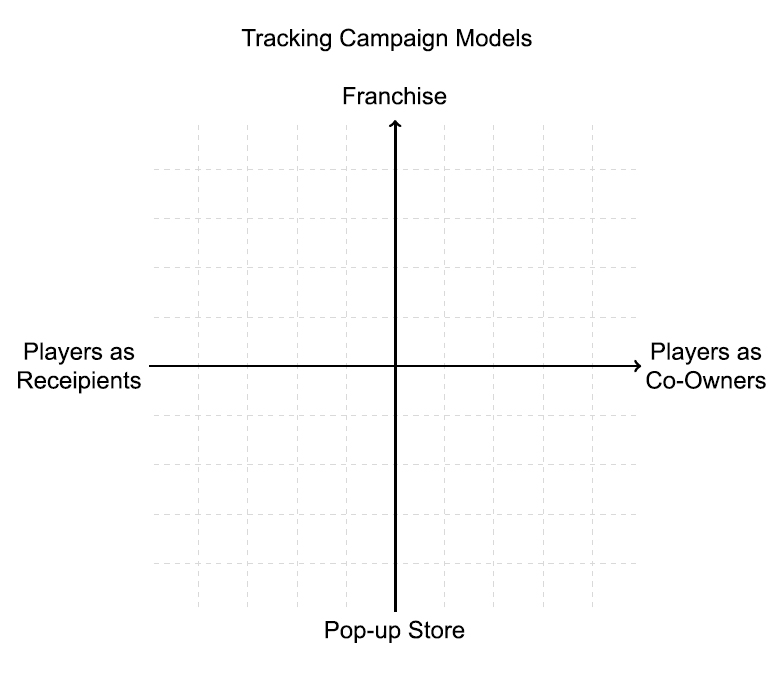

There are countless business models in the world, and just trying to find a comparison between the most popular business models and how a GM treats their players isn’t going to be as useful as making your own that fits your playgroup. The best way to easily illustrate the models described in this article is by tracking player and GM investments (the x-axis) and the campaign’s longevity and scale (y-axis). I’d love to hear where your favorite campaigns lie on these two scales, and where your ideal campaign lies.