Hello, everyone, and welcome to Guidance! I’m Alexander Augunas, the Everyman Gamer, and I’m back after a HELL of a week (not the “good” Hell of a Week, the kind of “Hell of a Week” that has you sitting in anxiety all week, eyes glued to the TV, wondering if you’re going to wake up in a democracy or a dictatorship in a few days). BUT HEY! Teenaged Wasteland! One of the most important parts of running Teenaged Wasteland for me is the idea that it’s a slice of life campaign setting, meaning that my players should get to roleplay the mundane parts of their characters’ day-to-day lives as much as the extraordinary parts. In fact, I would go as far to say that the mundane parts are MORE important than the actual adventures in Teenaged Wasteland, because ultimately that normalcy is the thing that my players are fighting for. If you want your players to feel attached to a place and it’s people, you need to give them time to build an attachment to those places and people, after all! So, let’s talk. How do you get your players invested in the day-to-day life of their characters?

The Pitch

Perhaps the most important part of running a game like Teenaged Wasteland is to make sure that the fact that slice of life roleplaying features heavily in your campaign is a major part of your pitch to the players. When you start a new campaign, you should essentially give a sales pitch to your players so they know whether or not the story is the sort of thing they’ll be interested in. In my opinion, a good pitch includes things like:

- What campaign setting are you using?

- What house rules are you using?

- Are there any parts of the character’s backstories that their characters need to have?

- What adjacent rules systems will you be using / what rules won’t you be using?

Campaign Setting

Obviously, your players are going to want to know where they’re playing. When I pitched Teenaged Wasteland to my players, I told them that I’d be using the Blood Space campaign, but they were allowed to build characters from the Pact Worlds campaign setting as long as their character had a reason that they were attending the Imperial War College on Tor. Of my seven players, only Coren wanted to be from the Pact Worlds setting; he chose right away that he was a street rat from Absalom Station, and that his reason for being in the Imperial War College was that his Parent sent him away to a Military School that was as far away as possible from him, using Coren’s own hard-earned credits no less! One of the fun roleplaying bits for Coren has been his discovery that the Imperial War College isn’t some correctional institution like he and his Parent thought, however; the Imperial War College has one of the finest private secondary educations in the entire system, so much so that most of the political and military elite send their kids there! The RP that ensued as Coren realized just how different he was from his new friends was something that really grounded him to the setting.

House Rules

It’s pretty rare that a GM runs their game exactly how it’s written in the Core Rulebook; most GMs have house rules. For Teenaged Wasteland, I had a number of House Rules and I was very adamant about making sure my players knew about them:

- Instead of the standard ability adjustments for species, all characters got +2 to one ability score of their choice. At their decision, a character could take a -2 to one ability score to gain a +2 to another, and the two +2 bonuses can stack (for example, you could have +4 to one stat and -2 to another). Starfinder has exceptionally tight math and not having good ability scores hurts. I wanted my players to be able to play any species they wanted without feeling like they made the wrong choice.

- I allowed my players to use my Species Reforged rules. It’s a little more power and a lot more customization. They liked it!

- I developed a Special Snowflake list of perks that they could have going into the game. It was basically a small way that they could tell me what kind of assets they had from their families and backgrounds that tied neatly into the campaign.

Backstory Requirements

For most campaigns, it’s great to just let your players play whatever they want. Sometimes, however, you have a story in mind that you want to tell that requires the players to fit a certain mold. For example, the 3PP Adventure Path “Way of the Wicked” requires the PCs to be criminals going to the worst jail in the land. This type of restriction can breathe creativity in your players, so it’s important to be willing to loosen those requirements a little bit so both you and your player end up with the kind of story that you want. For example, Teenaged Wasteland’s big backstory requirement is that every character needs to be young enough to be an attendee at the Imperial War College’s high school program; they need to be their species’s equivalent of a freshman, or a 15 year-old. Most of my players had no problem hitting this number, but where the story became interesting was that one of my players wanted to play an android. They’re built as adults, so at first android didn’t see, like a great back for this campaign. But then I sat back at got to thinking; isn’t a teenage just an adult with no experience? I decided, then that my player could play an android as long as he was younger than 5 years old; we went with 1 year old, and it worked!

Adjacent Systems

Your players should be aware of what other game mechanics you plan on using in their campaign, as well as which commonly used ones you might be skating by with. This helps to set your players’ expectations about the game so they know what kind of options are worth taking. For example, if you’re upfront with your players and tell them that your campaign is going to heavily feature vehicular racing rather than starship combat, your players will know that options that boost their ability to participate in vehicle chases are much more important than those that enhance starship combat. In Teenaged Wasteland, I presented a rules system for tracking how my players handled their grades (a slightly tweaked version of my work in 52-in-52’s Magical Academies product) and let them know that we wouldn’t be doing much starship combat because it didn’t make sense for a bunch of 15 year-old kids to have free reign of a starship. (That, of course, hasn’t stopped two of my players from begging for a starship at every opportunity, of course!)

The Hook

Okay, so you’ve told your players everything that they should expect in your campaign. They know what systems are important, they know where the game is taking place, all that kind of stuff. Ideally, the information you gave your players primed them for this next step—the hook. Ultimately, for your players to really care about the place they’re adventuring, they need to be given a reason to care about that place. It can be really, really difficult; some players are gonna resist your bait no matter how masterfully you cast it. But ultimately, isn’t that the secret? If you wanna hook a player, you gotta cast the bait.

Require A Backstory and Use It Heavily

This is the place I see GMs fail the most. If you want to hook your players, have them write a short backstory AND draw on it heavily. When you ask for a background, however, don’t just have your players write whatever and submit it to you. Target that feedback. When I first started Teenaged Wasteland, I told my players that their backgrounds had to meet two criteria: they needed to fill in all the information I gave them in a short form and their backstory couldn’t be more than 750 words (about 1 page). My form was super, super simple as well:

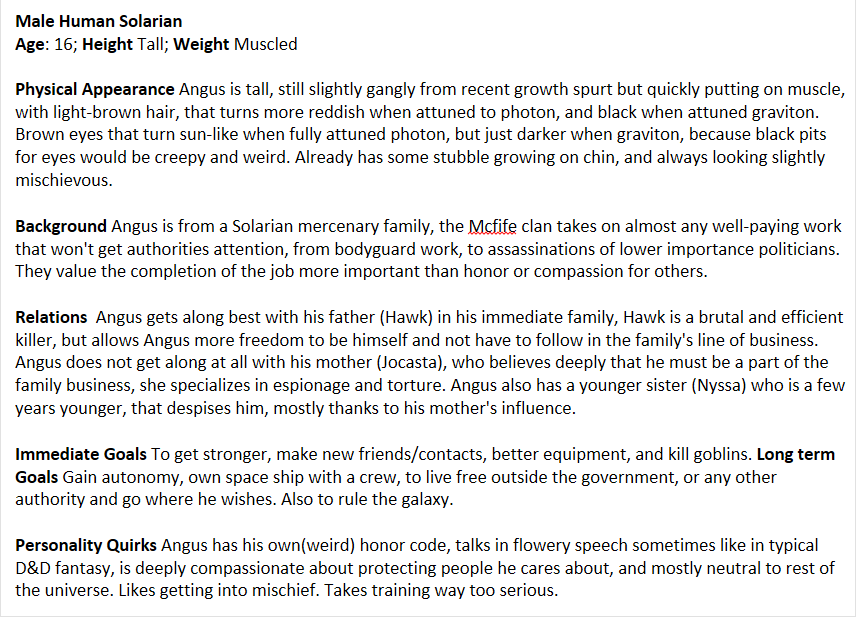

- Gender / Species / Class. This is the basic identifying information for the game.

- Age / Height / Weight. This is vital statistics; it tells me what your character looks like. Specifically, I asked for adjectives like “average” or “emaciated” rather than numbers; telling me 6′ 2″ doesn’t mean anything without comparing it to something else, after all. But telling me that you’re short and overweight does.

- Physical Appearance. This is a section for the player to describe to me what their character looks like. All of my players mentioned skin and hair, but some included clothing, some did eyes, and others did general demeanor. By letting your players describe what their characters look like, you learn what that players sees, which lets you note the things that are most important to them as roleplayers, which is a trick you can use to get them to buy into their world. For example, one of my PCs, Coren, mentioned that they wear trendy clothing. This tells me that wearing nice or stylish clothing is an important part of that character’s identity, so I know to include NPCs who comment on the character’s clothes or include clothes shopping as a slice of life thing the player might be interested in.

- Background. This is a short section where the player tells me some important information about stuff that happened to their character. Some told me about their families and their parents, some told me about experiences they had. Some told me very broad strokes about the character’s personality. Whatever you are told, this is another aspect of the character that’s important to the player, so this section tells you what sort of things you can do to add to the player’s slice of life experience.

- Relation. This entry is a quick place where the players can name any other characters they have a connection to. This can be other PCs or NPCs that the character knows and likes, and if you have a team of four players this can be a great resource for pulling helpful NPCs or building antagonists that can carry through an entire campaign for you! Whatever you choose, nothing gets your PCs more invested than when things are personal.

- Goals. In my write-up, I split this section in twain; immediate goals and long-term goals. The former are things the character wants to do now, and the latter are things the character wants to do someday. Knowing these two bits of information helps the GM establish rewards that motivate the PC into participating in the adventurer; this section is basically your PC telling you what motivates them, so take it seriously. If you use your players motivations to lead them along the story, they’ll follow you willingly rather than you needing to rail-road them along.

- Personality Quirks. This is a little entry I like to give my players so they can tell me something interesting or unique about their character. Quirks are usually the little things that the players do to help them get into character, the small details they can focus on as they work on building their roleplaying identity for the PC. It’s a really good idea to have personality quirks as a result.

Sample Backstory

Here’s an example of a backstory given to me for Teenaged Wasteland!

With this in mind, here are some things I’ve done with this backstory to help pull this character into Teenaged Wasteland.

With this in mind, here are some things I’ve done with this backstory to help pull this character into Teenaged Wasteland.

- Background: I did an entire story arc where the players had to spend a week with this character’s mercenary family. During this arc, I took a bunch of the basic ideas here, such as the fact that the entire family consists of solarians and that they value job completion over compassion to really give the players a good sense of how this PC got to be the kid he is. Needless to say, all the PCs left asking this character, “How on earth did you survive here for 15 years?!”

- Relations: In the team’s first starship combat, I had the enemy captain be this PC’s little sister. It was literally the first time I drew from this player’s backstory, and it was super clear that I caught him off-guard. Trust me, folks, your players give you this stuff but they never expect you to use it; USE IT. Their reactions regarding the fact that you read their stuff and liked it enough to make parts of their plot an important part of their play experience is incredibly satisfying.

- Immediate Goals: Originally I thought that the, “To Kill Goblins” bit was a joke, but the first time it came up in an RP I immediately grabbed on it. Humans in the Blood Space campaign setting have a bad history of being human supremacists, so the several times this character acted on those comments I had it be an immediate consequence for him; he was speaking to a catfolk boy at the time, and the catfolk spread around school to all the other non-humans to “watch out” for this PC. Using Discord, I was able to pass the gossip around to all the non-human PCs in the party, and later in the game when the party confronted an actual human supremacist, that same character made a comment to the PC along the lines of, “Oh, I thought you were this way too because you made that comment about goblins at gridiron practice.” Needless to say, this PC turned his tunes around after that encounter and even ended up bringing the school’s only space goblin NPC to Homecoming!

- Long-Term Goals: This one has been interesting, because literally the entire line is against the basic plot for Teenaged Wasteland. Most of the story is being kids with no autonomy, having to live under the rules and regulations of adult society and do what they say, when they say it. Part of my mission, then, is to give the player reasons to stick around, then give him the opportunity to take the freedom he wants and see what he chooses. Basically, a Han Solo moment where he’s delivered Leia to the rebels, has his ship repaired and is ready to go. Han could leave, but ultimately he stays to fight because ultimately, he believes in freedom and cares about his friends, I want to give this character a similar moment where he can choose—is leaving and getting to act on these selfish goals what he really wants, or does he want to stand with his friends and save the world?!

Looking Forward

Teenaged Wasteland is a huge part of my engagement with Tabletop RPGs right now, so I’m planning for a ton of my future content to focus around the campaign. Long-term, I think I want to talk a bit about how my special snowflake rules, as well as some of my tricks for impromptu GM storytelling. I also have written accounts of a vast majority of the RP and sessions we do, and I’m considering releasing those as content on Know Direction, but I haven’t decided yet. If you’d like to read the transcripts, so to speak, you should let me know by messaging @Alex on the Know Direction Discord! I’m never really sure how many people read these Teenaged Wasteland articles after all, and would love to hear what you have to say! For now, that’s all I’ve got. I’ll see you next time, on Guidance!