Welcome back to Phantasmal Killer, a blog delving into weird and fun game mechanics and how you can take advantage of them to bring new ideas to life at your tabletop. In each article I look at using a game system in unexpected ways to create unique or bizarre characters to pummel your players.

I have a personal philosophy in game design: You are what you model. If your game system is built around combat, most of your encounters will come down to fights. If your game system is built around skills, your players will wander through the story and sensibly flee from shoggoth. The results will vary from group to group—especially if you have a bard—but ultimately adventures will do best when they reflect whatever the system handles best.

But what about when you want to build an entire adventure around challenges your system doesn’t reflect?

There’s plenty of space for handling unusual encounters via roleplay and skill checks, leaving the details up to player imaginations and acting, but there’s also a lot of added tension when you build a subsystem to handle that interaction. Having some rules adds the same sense of tension and chance that combat normally has. But building a subsystem means investing a lot of time into creating new rules, playtesting new rules, and writing cool flavor text for your cool rules for your blog. If only someone had already built a cool rule system to do handle that cool mystery or romance subplot your wanted to run!

Someone has. The game designers!

Here’s the thing: Most games already have a fleshed-out combat system, already well-balanced and chocked full of adversaries. The only thing separating swordfight from a political debate is how you describe it.

Statting a Mystery in 5e

To adapt the combat system to other purposes, think about it abstractly: what does each element of the combat engine represent and how does that translate to its new purpose? Monsters aren’t just monsters; in an abstract sense they are an obstacle to moving forward with the story and achieving your goals. Stabbing them isn’t literally about bloodshed, it’s about using the tools available to overcome the obstacle in a direct manner. While my example uses fifth edition Dungeons & Dragons, you can use similar guidelines as an example to set up mysteries for Pathfinder, Starfinder, or your own favorite RPG ruleset.

Using your combat engine for mysteries, social combat, or any other chapter is largely an issue of determining how all the usual combat elements translate to your new format. In this case, we’ll rebuild the combat engine for a Scooby-Doo style mystery, but you can consider the same elements to re-paint it to suit your other plot-related needs.

In this case, I want a mystery encounter to be a fake monster—the Foxfire Phantom—terrorizing the town because someone wants the locals to flee so they can excavate a treasure buried beneath town square. The PCs, being roving adventurers, probably recognize that there’s no such monster as a “Foxfire Phantom,” and even if they don’t, still want to help defeat this strange beast that appears in town to terrify locals and destroy crops.

Mystery Stats

Translating combat statistics into a mystery (or other social/skill encounter) isn’t as scary as it might first seem. Here are the basics:

Mystery Rounds: Like combat, mystery time is measured in rounds, but mystery rounds are slower and more freeform, likely representing a few minutes to an hour of work; for slow mysteries (such as one with the heroes stuck on a slow boat), each round may represent several hours or even a day! The GM should decide how long a mystery round is. For the Foxfire Phantom, each mystery round is an hour.

Mystery Turns: Each PC involved in a mystery rolls initiative and takes a turn, and the mystery adversaries (see below) take their own turns as well, representing a hostile opposing force, bad luck, or stress affecting the PCs. As with a normal turn, a PC may take a single action (usually an ability test) and move; because mystery rounds are so long, a PC can generally move anywhere nearby unless circumstances require them to remain in one place; in a battle of the bands, for example, PCs will generally need to remain on-stage, and in the mystery takes place aboard a ship at sea, the heroes can’t leave the boat. Some mysteries may have a limited number of turns before they end. If the PCs do not deplete a mystery adversary’s hit points before this timer runs out, they achieve some mixed success determined by the GM depending on how well they did.

Mystery Attacks: PCs “attack” a mystery using ability checks—generally Intelligence-based proficiencies like Investigation and Arcana for “ranged” styles attacks that don’t require close proximity to the mystery and Charisma-based proficiencies like Persuasion and Intimidation for “melee” attacks that imply close interaction with others. Some mystery adversaries might allow the PCs to use other abilities, so think ahead if some aspect of the event could reasonably be “attacked” with Medicine or Sleight of Hand. The mystery adversary’s AC is the DC for these ability checks.

Mystery Hit Points: Mystery combat still uses hit points. Each mystery adversary’s hit points track the PCs’ progress toward their goal, and as each adversary is “killed,” the PCs gather that clue. The mystery adversary’s attacks inflict hit point damage on PCs as well, representing exhaustion, confusion, humiliation, or being discredited. PCs reduced to 0 hit points by mystery combat aren’t at risk of dying or even necessarily unconscious, but gain three levels of exhaustion and can no longer participate in the mystery combat, even to assist their friends—they’re too discredited, heartbroken, humiliated, or otherwise incapacitated to be useful to anyone for the time being. Hit points lost to mystery combat aren’t physical damage, and if a fight breaks out in the middle of an investigation, track the heroes’ real hit points separately from the damage they’ve taken from mystery combat.

If you want to go one step further, calculate a separate “Mystery Hit points” total for each hero by starting with their standard hit points, subtracting a number of HP equal to (level×Con mofier), then adding a number of HP equal to (level×Wis modifier)

Mystery Damage: Instead of weapons, mystery combat uses approaches, as in different approaches to solving a crime or gathering clues like searching the area, asking around, shaking down informants, interviewing witnesses, sketching the crime scene, etc. A successful ability test against a mystery adversary inflicts damage as if it were a successful attack, and each attack inflicts damage based on how relevant that approach is against the kind of clue: Usable (1d4 damage), Appropriate (1d8), or Ideal (2d6). PCs add their Intelligence modifier to damage as if it were a Strength bonus. You can add additional weapon qualities for especially useful approaches or those that suit a PC’s strengths and class abilities; you might decide a subtle approach like infiltration is “Heavy” for barbarians and fighters and so they roll those checks with disadvantage.

Mystery Surprise Rounds: If the mystery directly targets the PCs themselves, like framing them for a crime or robbing them, then the mystery adversaries get a surprise round to act against the PCs. Heroes can detect this “ambush” with a successful Wisdom (Insight) against the adversaries’ Charisma (Deception).

While not applicable to mysteries, if you adapt combat to other encounters like social combat, you can decide to use a surprise round for the PCs to reflect any precautions or planning they take ahead of time.

Mystery Spells: Normal combat spells are generally inappropriate for mystery combat, ending the encounter in suffering and pain. Spells that improve PCs’ abilities or make a target more receptive grant advantage on ability checks related to the spell’s effects. Charm person, for example, would grant advantage on Deception or Persuasion checks, but not on History or Intimidate checks. A mystery adversary saves as if it were an individual creatures; if an mystery successfully saves against a spell that targets it, the social faux pas restores hit points to the adversary as if the spell were a cure wounds spell cast at the appropriate level (spells cast to enhance the PCs during an mystery do not run this risk). You may instead adapt noncombat spells to mystery combat by assigning them effects equivalent to another spell of the same level; for example, a locate object spell to look for clues pierces right through deception and can effectively act like a scorching ray, inflicting ranged damage against one or more mystery adversaries.

Mystery adversaries can still use combat spells and abilities they have, reflecting their momentary tactics or chance complications as the story develops. A clue doesn’t literally make itself invisible, for example, but might be momentarily out of sight and more difficult to track down because the villain sets a fire to cover their tracks or an unrelate NPC cleans the room not realizing they’re destroying evidence.

Mystery Death: If mystery adversaries deplete every heroe’s hit points, the party isn’t dead, but the villain has effectively gotten away with whatever their sinister plot is and the heroes aren’t in a position to stop them: Maybe they finally sign the deed or escape with their ill-gotten loot while the PCs were flummoxed at dead-ends, or maybe the heroes make false accusations or social missteps that leave no one in town trusting them. You might decide that mystery death carries other, heavier burdens as well, like the heroes being framed for the crime or causing so many problems they must bribe officials to stay of ut jail, or the villain makes off with an object or NPC important to them.

Mystery Adversaries

The main targets that keep you from advancing in a mystery are the unknowns: the villain’s identity, their motivation, their prize, and how they do it. Once the villain is completely exposed, the encounter is defeated; we can move on to a separate combat encounter after this or Old Man Jenkins who runs the haunted carnival can just shake his fist in frustration.

But the secretive criminal himself isn’t the enemy you need to stat up. Instead, each major clue in the mystery is a “monster” in the encounter the heroes need to “defeat” to actually find and recognize its importance. Only once they have all the clues does everything become clear (in character).

Because heroes will generally walk into a mystery fresh and it will be their only major encounter of the day, you should lean toward building mystery encounters as Hard or even Deadly encounters.

Putting It All Together

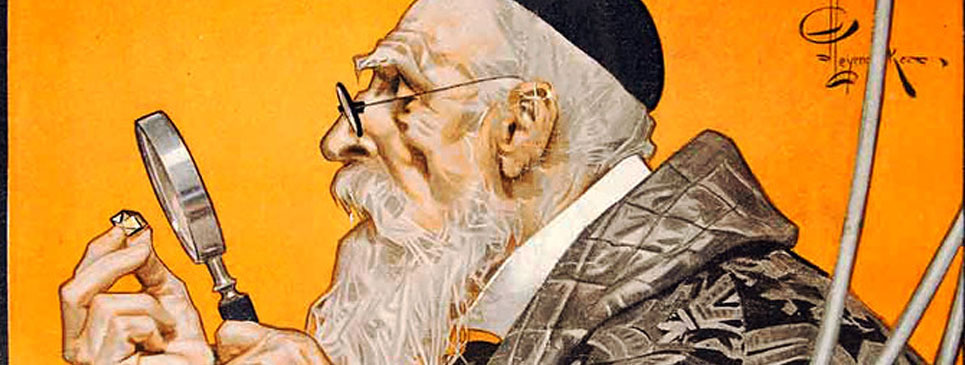

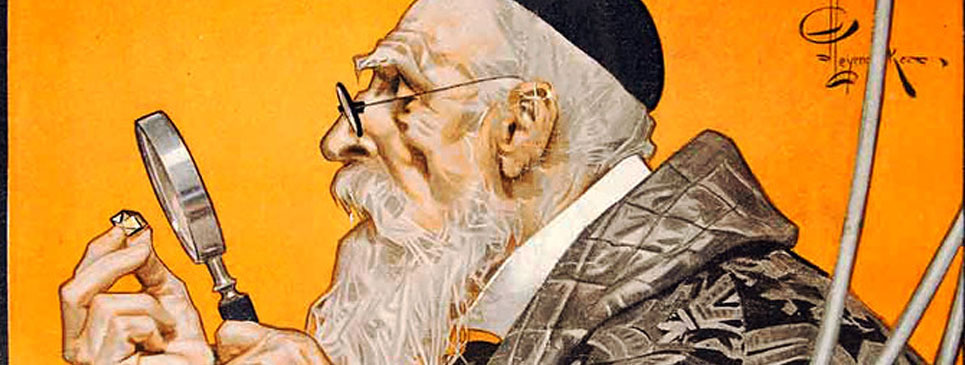

The heroes arrive in Goldwood just before the annual Harvest Festival only to discover no preparations are being made for the event and many locals are preparing to move. They can quickly learn that a glowing apparition locals call the Foxfire Phantom keeps appearing in town or the surrounding farms, terrorizing locals. His ghostly flames even light fields on fire, and most everyone in the small town is ready to flee. In truth, the Foxfire Phantom is Old Father Jenkins, who runs the old chapel outside of town. Jenkins discovered an old adventurer’s journal in that described a band of heroes a century ago who buried their treasure in the forest and planted a rare golden oak tree over it to eventually find their way back. This same golden oak now stands in town square—Goldwood was literally built around this rare and beautiful tree. He devised the identity of the Foxfire Phantom, using phosphorescent fungi spores from a nearby grotto, to chase everyone away so he could dig up the treasure.

The Mystery of the Foxfire Phantom is a Hard mystery combat for 1st level characters, giving it an XP budget of 300. I want it to have three major clues—three adversary monsters—that are key to solving the mystery: the old adventurer’s journal, the grotto and its glowing spores, and Old father Jenkin’s extensive gambling debts. These basically break down into three broad categories of physically searching town, physically searching outside of town, and learning about the people in town.

- The Journal: PCs who want to physically investigate in town are unwittingly “battling” the journal, which Old Father Jenkins dropped in town after his latest faux-haunting and has been kicked into a trash-strewn alley. The journal is easy to overlook and not especially vicious, so I’ll represent it as with a goblin. Each round of combat, the PCs fighting it need to succeed at a Perception check against a Stealth check to even try attacking it and making progress.

- The Grotto: PCs looking into the burned fields outside of town are unwittingly engaging the grotto clue and can find footprints (ghosts don’t leave footprints) leading to the burned fields from somewhere in the forests. Trekking through the forest is hazardous and might come with dangers for the unprepared, so I think a monster with poison sounds appropriate, like the Giant Wolf Spider. The poison damage represents the extra hazards inherent in the wilderness or might reflect literal poison from insect stings, snakebites, or poison ivy, and heroes can choose to resist that extra damage frome ach attack with a Wisdom (Survival) check instead of a Constitution save.

- Father Jenkins: PCs who start interviewing townsfolk to find out who has a motive are engaging with the Father Jenkins facts clue (not Father Jenkins himself), and I can represent this as one lump sum… OR I can break up the increasingly suspicious details about father Jenkins into a few smaller clues that get doled out one at a time, breaking one clue down into three Jackals. Essentially the heroes learn something about different townsfolk with every successful attack, and something about Father Jenkins every time they defeat one of the jackals: He’s a lot crankier than he seems on first meeting, he’s been advising people to move away from town to escape the Foxfire Phantom, and that he has large gambling debts with the traveling merchants who come to town every few months.

Once the heroes defeat all three clues, they’ve essentially solved the mysteries in this encounter. I’ll let them set up an elaborate trap to snare the Foxfire Phantom, just for fun, and then they can unmask Father Jenkins in front of the rest of the town!