One of our jobs as GMs is to get and keep our players engaged in the adventure. Some GMs will argue that it’s as much on the players to come ready to engage as it is on the GM to engage them, and I admit that I’ve been GMing tables where all I want to do is shake them and say “roleplay, curse you!” But I’ve also been in audiences where stand-up comics insist we should be laughing. Obviously that’s why we’re here, but telling us over and over to laugh isn’t funny. So how does a GM convince players to engage?

Highlight

Sometimes details are missed. Maybe your players were on their phones, maybe they were thinking about a spell and only half listening. Just like someone seeing a comedian to distract them from bad news, why they missed an important detail isn’t as important as the fact that an important detail might have been missed.

Many video games react when players idle for a few seconds. Dialog from a cut scene is repeated, the mission log flashes, light shines on a door or item. If you’ve ever felt directionless in a video game you might guess that the time to trigger a reminder is 10-30 seconds but it’s usually closer to 3-5. In person, 10 seconds is probably a more reasonable wait period. Players have different information to process than GMs, and although the onus to engage the players is on us, the thrust of the story is on the players. Giving them a silent ten count to process information eliminates the possibility that they are silently thinking and prevents the perception that you’re leading them by the nose.

As usual, my advice is to flavour these reminders with context and the player’s point of view. “As you sit there, contemplating your situation, you’re reminded of the desperation in the cook’s voice when she asked you to keep an eye out for her favourite ladle” is more engaging than “I said there’s a ladle among the loot. A ladle!”

Check In

Silence and inaction is not always a result of not listening or lack of understanding. It can be a situation I’ll call “waiting at the train station”. Railroading is commonly seen as the cardinal sin of GMing. The line between making players do what you want them to and expecting players to follow the plot hooks is finer than you might think, and there might be more factors as to why they might not be following the plot than you realize. Maybe moving on to the next adventure point makes the player feel they have to abandon a subplot or something they were hoping to accomplish that they haven’t even brought up yet.

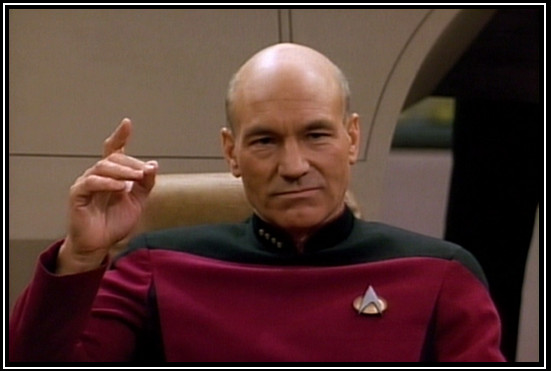

Recently, my friend Will was GMing a Starfinder Society game and found his group surprisingly noncommittal when told to talk people out of dying (details kept vague to avoid spoilers and for comedic purposes, so you should be laughing because it’s funny why aren’t you laughing?). Effectively, Diplomacy checks would save lives. And yet no one wanted to roll. He made sure everyone understood the rules of the situation and asked what everyone was doing. Silence. He prodded and found out that the highest Diplomacy bonus in the party was +2, and that no one wanted to be responsible for the failure. He stressed that inaction was as bad as failure and finally got a player to make the roll.

Consequences

In the video game example, not doing anything means the game must wait for the player to act. Yes, I said earlier that players control the thrust of the action, but that begins and ends with their agency over their PC. If you tell the PCs that a flaming cart is barreling towards an important NPC and the player chooses to do nothing, that cart is going into that NPC.

However, inaction takes a flexible amount of time. Yes, if the PC continues to do nothing, either the NPC gets crushed or a third party intervenes and saves the hero a consequence of their action by doing the heroeing for them. But you can stretch that inaction out and drive home what they are allowing to happen. Most checks come with a threat of failure. Instead of going straight to consequence X for inaction, you can move the dial slightly closer to X to let the weight of X sink in.

A pig farmer’s prize swine steps in front of the cart en route to the NPC and is obliterated. Flames fly off, setting nearby foot stands on fire. The NPC’s grandchild shouts out a tear-swelled “Grandpa!” The NPC looks up at the cart, his eyes reflecting off a smear of pig blood, making eye contact with the inactive PC that screams “why aren’t you helping me?”

Read The Room

Finally, you might just be setting the wrong expectations for your players. We make a lot of assumptions that players will remember specific moments from past adventures, that they understand the game and campaign setting as well as we do, and that your players understand the information you present as you intend them to.

If you feel a dramatic moment has fallen flat, remind them in the form of a flashback. Connecting the dots does not come off dull or condescending if there’s a light show or explosion at every dot connection.

Understanding the game world or rules just takes recontextualizing. Remember the scene in Road Trip where Paulo Costanzo’s Rubin explains Greek Philosophy to Breckin Meyer’s Josh by way of an extended pro wrestling metaphor? Do that. Drawing on history, popular culture, common ground, or just knowing how they think. It’s like when I play Catch Phrase and I need my wife to guess “dog” I say “opposite of cat”.

Finally, how players understand the information is the trickiest of the above circumstances, and is a pitfall of the shared storytelling experience that is roleplaying. I remember one PFS scenario I played in where my faction mission asked me to talk to a certain character, we’ll call him Mr Jones. At the end of the scenario I’d never met Mr Jones, and I expressed my confusion to the GM. He said Mr Jones was right at the beginning, and that he gave me plenty of opportunities to talk to him. Confused, we walked through what happened. The scenario referred to the character by his full name, we’ll say John Jones, in the intro, then only as John throughout the scene he appeared in. But my faction mission only referred to him as Mr Jones. So to the GM, whose GM knowledge allowed him to understand the situation better than my player knowledge, I was failing to engage. To me, the GM was sitting there expectantly, and I wondered who he was waiting on.

The GM chose to move on, and I do not blame him for it. I would have done the same in his position. Having been in my position, though, I now know that if a player is not engaging when I expect them to, it’s worth taking a moment to explore it. As long as that exploration is not accusatory, because there are enough reasons why a player is not engaged that we as GMs shouldn’t take it personally.