People ask me: how do you find the time to write 12,000 words for an adventure? Planning. There are a few techniques you can use to make sure your hitting your word counts and getting your writing turned in on time.

Set Goals

If you sit down to write and don’t have a goal, how do you know when you’re done? How do you know you’re on track to finishing on time? By setting goals you can create a benchmark for how your writing is going and knowing if you’re ahead of schedule, behind schedule, or right on track.

I like to create my goals over the course of a week, that way I don’t beat myself up too much for missing a daily goal. I also try and use more nebulous, but achievable, goal. For example:

- Week 1 – Expanded Outline Due: encounters/creatures selected, maps selected

- Week 2 – Basic Document Format Completed; Writing Blobs completed

- Week 3 – Write “risky” sections including new encounter styles & major plot points

- Week 4 – Milestone Due

- Week 5 – First Draft Completed; Map Created

- Week 6 – Revision Completed; Map Revision Completed

- Week 7 – Final Turn in Due

Lets break down what those mean. This goes back a little bit to my writing process and how I tackle large projects.

Expanded Outline

This is where I really go through point by point in the adventure, listing out the events of the adventure as well as the encounters that take place there. It’s generally in traditional outline format and lists not only the locations, but major NPCs (with names, if possible), creatures the PCs will encounter and likely combat, and any pre-published maps I plan on using vs which locations I’m going to need custom maps for. This is very much in the early planning stages so that my developer and I are on the same page going forward. I want there to be very few surprises for them.

Basic Document Format

I like to start by turning the outline into the sections and subsections for my work with all of the appropriate formatting. This takes more work than it seems like it should take, which is why I like to get it out of the way first. Then the rest of my writing can concentrate on content instead of format. This also acts like an outline in away in that it already has section names and breaks down the basic organization. It helps me see the entire thing without the “meat” of the adventure and just the “bones” holding it all up. If I have any major changes I need to make, I’ll often notice it while getting my document set up.

I like to start by turning the outline into the sections and subsections for my work with all of the appropriate formatting. This takes more work than it seems like it should take, which is why I like to get it out of the way first. Then the rest of my writing can concentrate on content instead of format. This also acts like an outline in away in that it already has section names and breaks down the basic organization. It helps me see the entire thing without the “meat” of the adventure and just the “bones” holding it all up. If I have any major changes I need to make, I’ll often notice it while getting my document set up.

Writing Blobs

That’s just what I call them. These are the sections that say things like “The PCs fight pirates, one of the pirates has a dog.” These help future me decide where I’m putting key information so I don’t repeat myself, and act as a reminder to put in important information or mechanics: “If the PCs convince the mayor to help, they get a bonus such as free gear.” When I go back later to flesh them all out, then I know what’s supposed to go where and I’m not just trying to guess at where I include the mayor’s secret past as a pirate.

“Risky” Sections

Sometimes I like to try something new, like an experimental encounter or something that has new mechanics. I try and write these sections first along with any major plot points or twists. This is so that I make sure the hardest part of the adventure is written first and I’m not holding the hardest content for last. This is also so that my developer can review the “risky” material and ensure that they agree with my mechanics or plot development points. A developer is going to be much more likely to have notes on an experimental encounter or custom stat-block than on the description of a random room.

Milestone Due

Here’s where I get everything together for my developer to review. Most publishers will have a review process somewhere along the line to ensure you’re writing is on-track and you’ve not gone too far off the rails. I usually try and make sure everything has a least a full writing blog (see above) and all of the risky sections are 100% written and formatted, as if ready for final turn in. This will give them the best view of my work and most fair critique. I also try and get them any custom stat-blocks from NPCs or creatures, because I want them to review them as well. If they think I’ve abused the mechanics and made an NPC far too powerful, I’d like them to tell me while I still have time to correct it myself, rather than making them do it after the final turn in.

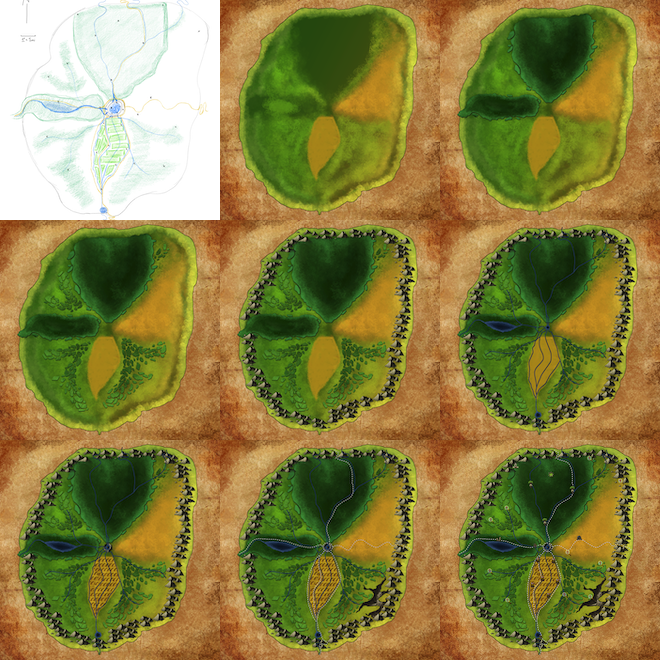

First Draft and Maps

Ah, we finally get all of the text finished, no more writing blobs. I also usually try and get my maps completed by this point as well. You don’t want to rush it with the map, and you usually want to change something about a week or two after you’ve drawn it. Give yourself time to take a second look at it, decide it’s garbage, and then revise it.

Revisions

The revisions stage is about 2nd and 3rd drafts, but it’s also about checking word-count. Making sure you’ve delivered all the information you think a GM will need to run the scenario. Answered any questions you can about NPC backgrounds and motivations, and covered the DCs and skills a PC is most likely to use to overcome an obstacle. You might even make sure you have all side-bars needed for your adventure. For Pathfinder and Starfinder Society scenarios that means 4-player adjustments. This is also when I do final loot calculations to ensure I’m including the right amount of swag and that anything the PCs earn is relatively evenly spread throughout the adventure with a little bit more weight for the final encounters.

The revisions stage is about 2nd and 3rd drafts, but it’s also about checking word-count. Making sure you’ve delivered all the information you think a GM will need to run the scenario. Answered any questions you can about NPC backgrounds and motivations, and covered the DCs and skills a PC is most likely to use to overcome an obstacle. You might even make sure you have all side-bars needed for your adventure. For Pathfinder and Starfinder Society scenarios that means 4-player adjustments. This is also when I do final loot calculations to ensure I’m including the right amount of swag and that anything the PCs earn is relatively evenly spread throughout the adventure with a little bit more weight for the final encounters.

Final Turn In

I usually like to do one last look at the adventure, reading it from beginning to end. Sometimes I’ll find myself repeating myself. Sometimes I’ll find that I never mentioned that the mayor is a dwarf, and that’s kind of important. Doing one last read-through from the point of view of the GM who’s prepping the scenario will help tremendously.

TaDa! You did it! You’ve scheduled out your adventure. Now you just need to write the dang thing!