In RPGs, there are two basic structures for an adventure: linear and non-linear. The GameMastery Guide (pg. 36) also includes unrestricted, but I see this as a variation of non-linear. So what are these adventure structures and what considerations do we need to make when writing them?

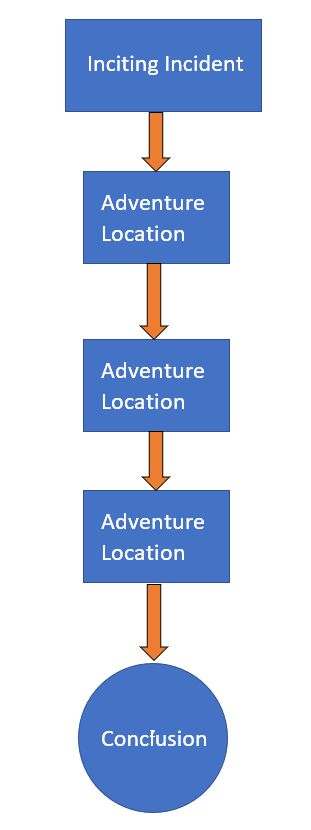

Linear

This is the most common type of adventure structure, often called a railroad structure. This is where the players go from plot point A to B to C, advancing in a very specific order. The example in the GameMastery guide shows: Monsters attack town > Witness gives directions to monster lair > Discover monster lair > Monster ambushes adventurers > Defeat the monster!

This is the most common type of adventure structure, often called a railroad structure. This is where the players go from plot point A to B to C, advancing in a very specific order. The example in the GameMastery guide shows: Monsters attack town > Witness gives directions to monster lair > Discover monster lair > Monster ambushes adventurers > Defeat the monster!

These are generally the easiest types of adventures to write and run as each location or plot point leads directly to the next location or plot point. Clues and game elements are laid out to lead the PCs down a specific path. This can sometimes feel restrictive to players who want to strike out and come up with their own solutions to problems, but also runs the most efficiently. Linear adventures are generally easy to guess how much time it will take at the table, which is why this structure is used so often in organized play scenarios.

If you’re new to adventure writing, I’d start with this sort of adventure as it lets you control all the elements of the adventure and you don’t have to worry too much about what the PCs are going to do to “throw it off the rails.” Develop your simple plot that takes the players from point A to B to C. Make sure the plot is logical and that there are obvious clues for the PCs to find to bring them from A to B to C. Some examples might be eye witnesses telling the PC where the monsters fled to or what part of the forest people avoid lets they vanish. The PCs then get a clear picture of “where they’re supposed to go next” to continue the adventure.

Things to look out for are being too “on the rails” where there are no considerations for alternative ideas. Be sure to include phrases such as “or any other creative solution the players devise” and “or any strategy that allows the PCs to avoid notice.” These give a GM running the adventure with a more strict interpretation of the rules know that flexibility is allowed, even if the core adventure remains the same. If there are alternative solutions that you think of, be sure to mention them in the adventure. This gives the GM a heads up that the players may come up with some less obvious solutions to a problem.

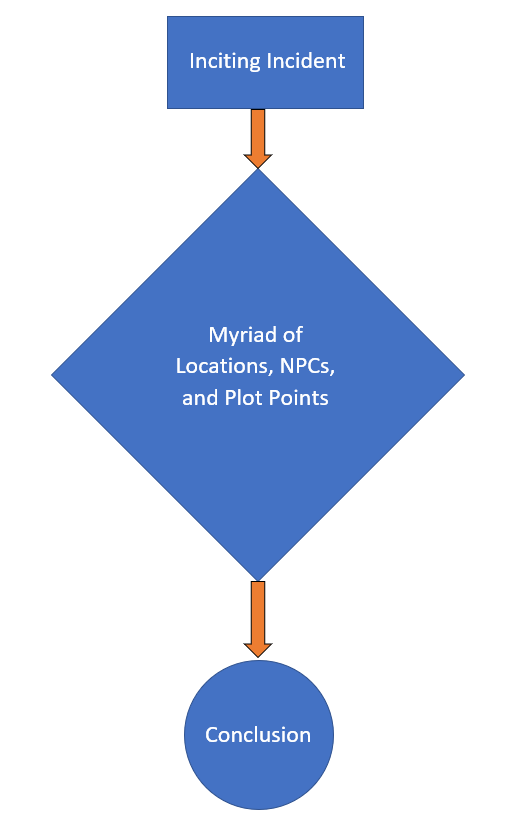

Unrestricted

This type of adventure allows the most table variation as players are given a huge freedom of choice for what to do next to solve the problem that the adventure poses. This is often called a sandbox, as players are left to play around in the game world however they see fit. Often they’re given the first part of the plot through an inciting incident, but where they go from there may vary significantly. The GameMastery guide calls this an unrestricted adventure, though people use the term sandbox far more often in common parlance.

This type of adventure allows the most table variation as players are given a huge freedom of choice for what to do next to solve the problem that the adventure poses. This is often called a sandbox, as players are left to play around in the game world however they see fit. Often they’re given the first part of the plot through an inciting incident, but where they go from there may vary significantly. The GameMastery guide calls this an unrestricted adventure, though people use the term sandbox far more often in common parlance.

When writing a sandbox adventure, you need to keep in mind all the various strategies a party might use to solve a problem. Because there are fewer guidelines for what the PCs to do, as the author you need to include several clues and hints that suggest a course of action. A strange note, a bit of torn cloth, a muddy footprint with an odd coloration, and a witness describing a strange sound all give the PCs different elements to investigate. Have some solutions in the adventure, such as skill checks and NPCs who can answer questions, as well as information for what to do if the PCs go off on a tangent.

These types of adventures rely heavily on GM interpretation of the adventure content and management of the players to keep them on a successful path. Your writing is aimed at giving the GM tools for handling different situations and recommendations for how to move the adventure forward rather than scripting events. Describing locations, NPCs, items, and even time-tables for actions happening outside of the PCs control all help the GM adjudicate the adventure.

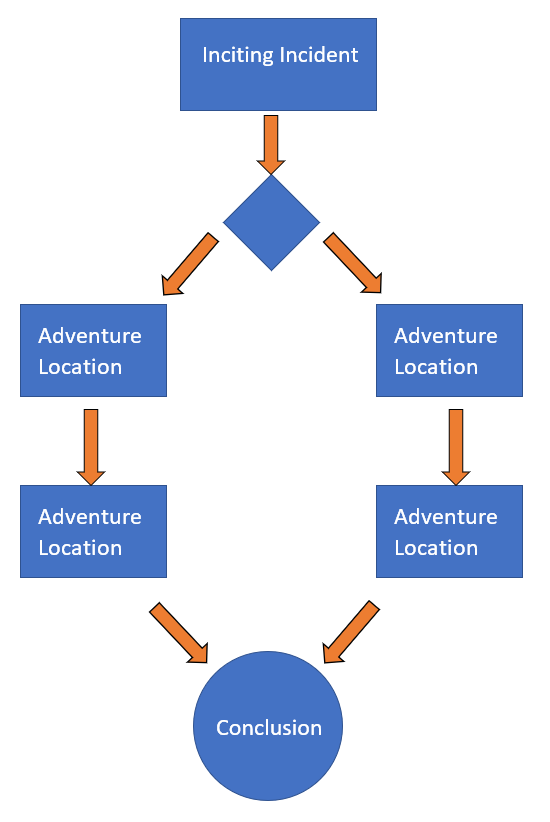

Non-Linear

The GameMastery Guide lists a third structure for adventures called non-linear. Though a sandbox is certainly non-linear, they use this description to talk about an adventure designed like a flow-chart. Non-linear adventures often have 2 or 3 distinct paths the PCs could take, or a list of objectives the PCs must complete but they can complete these objectives in any order. After you’re comfortable writing a linear adventure, move on to non-linear adventures.

The GameMastery Guide lists a third structure for adventures called non-linear. Though a sandbox is certainly non-linear, they use this description to talk about an adventure designed like a flow-chart. Non-linear adventures often have 2 or 3 distinct paths the PCs could take, or a list of objectives the PCs must complete but they can complete these objectives in any order. After you’re comfortable writing a linear adventure, move on to non-linear adventures.

Writing these adventures requires you to use a mix of the strategies for linear and unrestricted structures. At points where the PCs have a decision to make on what course of action to take or what objective to complete first, you want to write the adventure a bit more like a sandbox: give them information about the game world and the plot, then let them decide where to go next. Once they’re on a path, the action often becomes much more like a linear adventure until their current objective is complete.

Wrapping it Up

Each of these structures starts with an inciting incident that sends the PCs on the adventure and ends once the PCs meet the objective that solves the problem the adventure is posing. The only differences are how the PCs get from A to C. Once you’ve mastered these forms, you can take a look at the story you’re writing and find the best structure to tell that story.

Very cool and clear summary!

Oh, thank you. I’m glad you got something out of it. 🙂