Now that you know your role and have basked in your power, it’s time to bring you back down to Earth, my fellow GMs. In order to do our job, and enjoy all of the benefits of being a Game Master, we need to accept the obligations that go along with them. Everyone’s fun at the table depends on the work we put in. There’s a reason GMing as a paid position has been a topic of discussion for all of roleplaying games’ existence but player as a paid position is basically just a strawman argument. GMing is a more responsible flavour of fun.

The Basics of Game Mastery

Part 3. Game Master Responsibilities

In order to ensure that everyone at the table has fun, you need to ask yourself something:

What Is Fun?

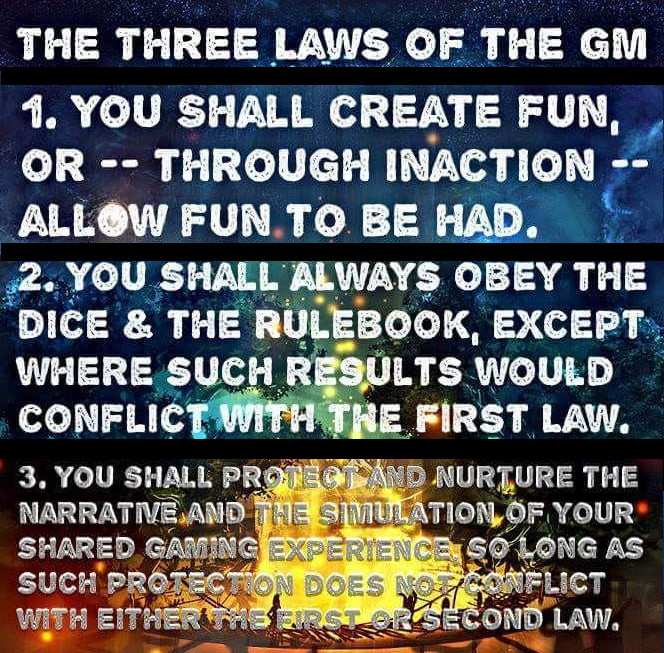

I recently shared this meme, borrowing from Asimov’s tiered Three Laws of Robotics, on Facebook:

Someone replied that “This assumes everyone’s idea of fun is the same.” To which I disagreed, so he fired back with arguments including “This even assumes the Group is completely Homogeneous,” “It’s okay if everyone isn’t having fun every second,” and “The Story isn’t always fun. Often it’s horrific, sad, serious.” I pulled my chute on the conversation at that point, since he was arguing against interpretations that I just don’t think the meme was saying. Primarily, “You shall create fun” does not mean everyone is having fun every second. It means through action or inaction, some measurement of the group’s fun quotient increases.

But I do think “The Story isn’t always fun. Often it’s horrific, sad, serious” bears a closer look. Because if I’m playing a game where I expect horrific, sad, and serious moments, then I appreciate when those moments come to pass. It may seem contradictory to say I’m happy when a game makes me sad, so in the name of pedantry, I suggest this alternative:

You shall pay out player buy in, or –through inaction– allow player buy in to pay itself out.

To be clear, I’m perfectly fine saying I’m there to have fun, and even a serious game can be fun. So, for simplicity sake, I’ll keep calling “paying out player buy in” fun.

Delivering Your Table’s Brand of Fun

Different people play the game in different ways and for different reasons. A gaming group is a compound of the various elements and expectations each person -ourselves included, my fellow GMs- bring to the table. In order to deliver on the first law of the GM, we need to understand the parts and the whole of what we and our players enjoy, and how they relate to one another.

Deciphering your table’s idea of fun may sound like it takes social intelligence, but here’s something to remember: You already have something in common with your players. At the very least, it’s a preference for your game system or setting. Outside of organized play, there’s also a good chance you’re friends with most if not all of your players. Just knowing them tells you a lot about how to entertain them. If you’re not sure, it’s good to define what everyone likes about roleplaying before the game. This can be during Session 0, or in a pre-session chat at an organized play event.

Not everyone has the introspection to put into words what they like about their hobbies. I tend to lead with what I know to be the controversial ways I have fun with my games. “Just so you know, I tend to get colourful and visceral when I describe damage. But if anyone thinks that’d bother them, I can tone it down.” Give an example of the language you use to communicate ideas and what kinds of ideas might need to be brought up.

Like the person replying to the meme I shared, you could worry about the melting pot of different tastes at your table. In my experience, the average player understands that they are a fraction of the number of people at the table and expect an equal fraction of attention dedicated to their specific needs. A dramatic player might get antsy if a pre-adventure scroll shopping scene goes on a little long, just like a tactical player might scoff at how long the banter before the boss fight takes, but a quick “we’re almost done” does wonders to reset a player’s patience. If a player is a spotlight hog, frame it as the other players needing to get their fair share instead of slapping their hand for wanting more than their share. “I’ll get back to you soon, but players X, Y, and Z haven’t had a chance yet.” If that doesn’t work, going clockwise around the table clues the needy player in on when to expect their time for your attention.

Player Agency > Your Plot Twist

As discussed in part 1, we’re not really narrators or storytellers, we’re the fusion point at which disjointed stories intersect. It’s important to remember this when crafting your plots. If you’re anticipating your players’ gasps when you pull back the curtain and reveal the truth behind a lie they all believed, I can almost guarantee you will not get the reaction you’re expecting.

Don’t cheat at Guess Who. If your players ask “Does the secret villain have brown hair,” don’t deny them their win and change the villain’s hair to blonde. Don’t throw an invisible ball. Your description paints the pictures your players are imagining. Obscuring an important detail to keep your players from paying attention to it is abusing your power as their access point to the world you all share. This is especially true if you have to cheat to pull off a big moment.

A couple of examples of this from video games come to mind. In Skyrim, I was investigating a murder. When I entered the murderer’s house, he let me go everywhere but upstairs. Which makes sense, narratively, but that’s not how anywhere else in the game works. Someone had to program an invisible wall into just that scenario so I couldn’t do something I wanted to do and should have otherwise been able to do. Similarly, in Arkham City, Batman has Detective Vision that lets him see through walls. I approached a dead end that didn’t feel right. Detective Vision didn’t show anyone inside the room or on the other side of any of its walls. I still spent a long time at the entrance, going through my inventory to see if there was anything that could trigger a trap. Nothing. So I walked in. A giant muscular hand punched through a wall and grabbed me. A wall I should have been able to see through but couldn’t, but he could see me somehow. In both cases, whatever reaction the scene was intended to evoke was replaced by annoyance because I did everything right and the game didn’t care. With a video game, that’s forgivable. It’s how they’re programed. When a GM does it, it’s irresponsible.

We discussed in The Basics of Game Mastery Part 2. By The Power of Game Mastery how your players will do more of what you incentivize them to, even unintentionally. They’ll avoid doing what you punish them for as well. And if you punish them for trusting you, expect a slow, adversarial game. The better we are as GMs, the less our players remember that there’s a power difference between us. And a twist risks reminding them not to trust us. Or, as Perram recently put it on Twitter:

I've stopped using friendly NPC betrayal as a plot device. Because PCs think all NPCs will betray them and games grind to a halt. Just like every freaking door in a dungeon.

— Jefferson Jay Thacker (aka Perram) (@jaythacker) February 21, 2022

Pay Out What You Buy In

GMing is fun, but the responsibilities can make it a lot of work. If you find yourself giving more than you get, see if you can find ways to give less. A lot of responsibilities not related to running a game often fall on our laps. Asking someone else to schedule the game or setup an online space for it, designating a player the rule researcher or initiative tracker, asking for access to a player’s massive miniature collection. We shouldn’t be spending more time, money, and mental energy on a game than we have to. We’re all in this together with our groups, don’t be afraid to ask them to share in the responsibility.

Every two weeks, Ryan Costello uses his experience as a Game Master, infused with popular culture references, to share his thoughts on best GMing practices to help his fellow GMs. Often deconstructing conventional wisdom and oft repeated GMing advice, he reminds his fellow GMs that different players play the game in different ways, and for different reasons.