It’s funny, ever since moving from D&D 3.5 to Pathfinder instead of D&D 4e, I’ve felt less connected to the Dungeons & Dragons brand. Whereas once I would have worn a t-shirt with a draconic ampersand, I no longer felt comfortable implying I was a D&D fan. Fantasy TTRPG fan? Absolutely. But Dungeons & Dragons specifically? Zero connection.

OK, one connection.

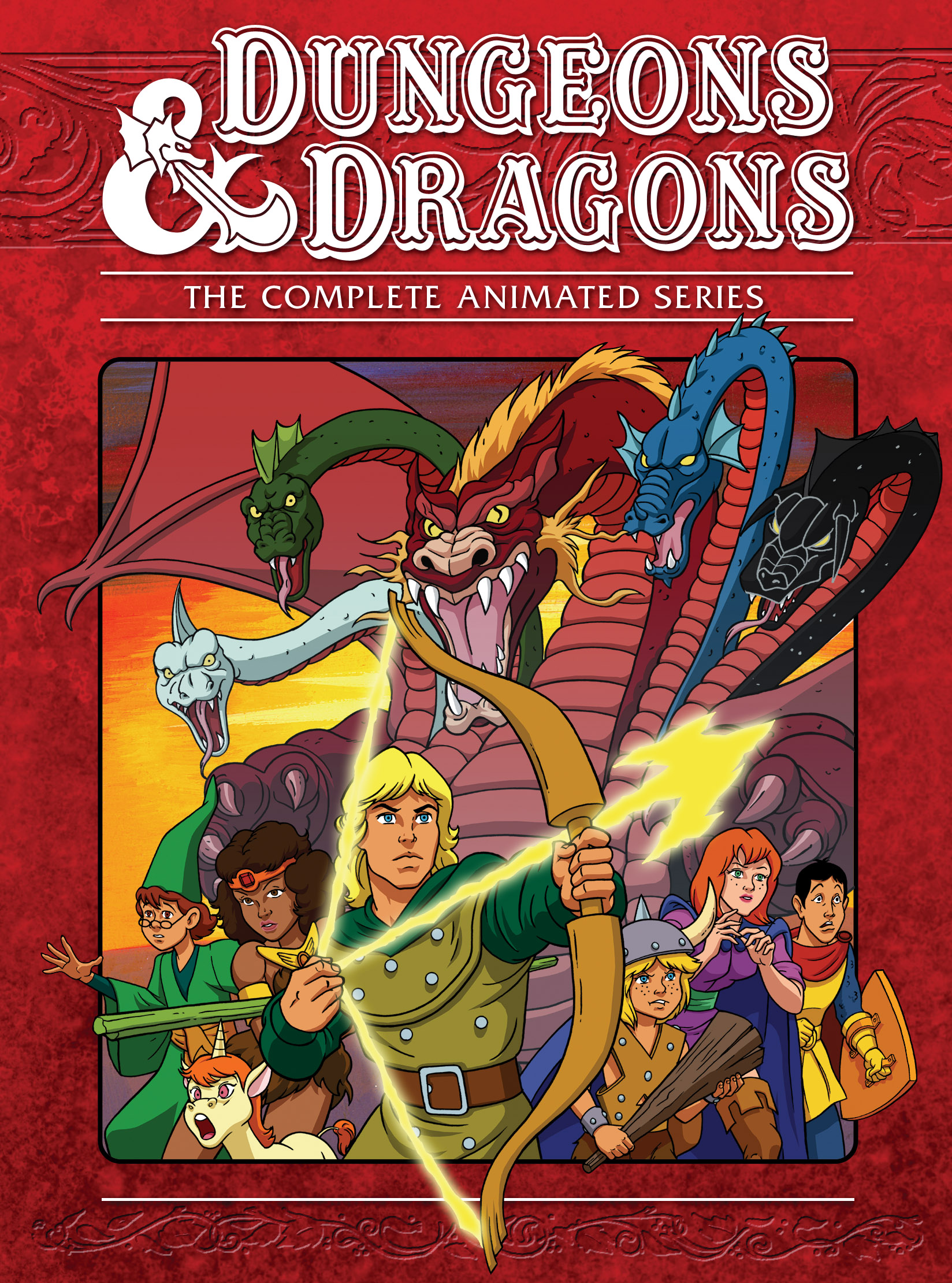

The Dungeons & Dragons Animated Series

I’ve said before that I was introduced to D&D on a whale watching trip in high school. That’s when my classmate Geoff introduced me to the game, but it was Hank, Diana, Eric, Sheila, Bobby, Uni, and most of all Dungeon Master who introduced me to Dungeons & Dragons.

For years, it’s seemed like D&D’s brand managers skied away from the Dungeons & Dragons animated series. Even though D&D dealt with the Satanic Panic against the game around this time, the cartoon wasn’t affected by the fallout to James Dallas Egbert III’s death (despite rumours that this, and not low ratings, lead to the show’s cancellation). Fortunately, Hasbro announced new action figures in multiple scales and styles based on the animated series. Considering they could be focusing all their efforts on the upcoming Dungeons & Dragons movie, I appreciate them acknowledging the cartoon as part of the brand’s lineage.

For years, it’s seemed like D&D’s brand managers skied away from the Dungeons & Dragons animated series. Even though D&D dealt with the Satanic Panic against the game around this time, the cartoon wasn’t affected by the fallout to James Dallas Egbert III’s death (despite rumours that this, and not low ratings, lead to the show’s cancellation). Fortunately, Hasbro announced new action figures in multiple scales and styles based on the animated series. Considering they could be focusing all their efforts on the upcoming Dungeons & Dragons movie, I appreciate them acknowledging the cartoon as part of the brand’s lineage.

And it’s not like the animated series lacked pedigree, with voice actors like Peter “Optimus Prime” Cullen and writers like Steve Gerber, formerly of Marvel comics. It’s an action adventure series that leaned into fantasy at a time when its contemporaries stopped at fantastical elements, still holds up today, and left an impression on its viewers.

Today, we’ll be looking at what you can learn from how the Dungeons & Dragons animated series taught a generation of viewers about Dungeons & Dragons.

Entering A New World

The main characters magically teleport from an Earth amusement park to the realm of Dungeons & Dragons. There, a benevolent Dungeon Master gifts them with weapons and assigns them roles.

In retrospect, the smartest decision series creator Dennis Marks and developer Mark Evanier made was to make the main characters of Dungeons & Dragons teens taking on the roles of D&D classes. The step into the meta made it more than just a fantasy cartoon with D&D elements. It paralleled the Dungeons & Dragons RPG experience.

Not only was this a thematic choice, it served a narrative function. During the intro, after encountering a winged horseman with vampire vibes and one horn, Diana asks “who was that?” Dungeon Master explains “That was Venger, the force of evil.” By making the main characters fish out of water, their questions tell the story of their confusion. Exposition becomes part of the plot, especially when phrased as a riddle by their mysterious mentor.

Teaching Your Players Through Their Characters

How do you inform your players about your campaign world? Do you write a campaign document? Create a wiki or use a campaign manager? Cite the publisher material you’ll be drawing from?

Some players find such techniques effective. Others feel like you’re assigning them homework. You may get mad at the players who don’t invest their time away from the table into your game, my fellow GMs, but remember that different players play the game in different ways and for different reasons. Maybe they don’t have time for the game outside of game night. Maybe they struggle with homework, and they play RPGs specifically to escape it.

Consider running a prelude session. Every player brings a character to the table who isn’t from your setting. Over the next few hours, teach them your setting or the rules of your game in world, through a guide, context, and player character driven exposition. Instead of expecting a player to read an extra chapter of rules just because they thought wizards look cool, have a magic shopkeep explain the secrets of magic to the wide-eyed commoner they’re playing in a prelude. You could even revisit these unheroic PCs periodically to inform their heroic PCs of shifts in the landscapes of your campaign.

Making It Their Own

Going back to the opening, the kids run away from Tiamat and into Venger, meeting the series’ two main villains. Once comes from D&D lore, the other the creators made up. This trend repeats through the series. They create their own characters, creatures, and locales. They use established D&D game content, like orcs and beholders. They even adapted original characters from the unrelated D&D action figure line, like Strongheart the Paladin and (the G.O.A.T.) Warduke.

Make It Your Own

Just because you’re using published material or established lore doesn’t mean you can’t put your own spin on it. This might seem obvious, but it’s where I struggle the most with written adventures. I think it’s two disconnected parts of my GMing brain that many of you have fused together, my fellow GMs. But if the D&D animated series showrunners could bridge between original, established, and otherwise adapted content, maybe I can too!

In Media Res

Remember how the series kicked off with an episode about the kids getting on that roller coaster only to get magically teleported to a fantasy realm? Where they meet the major players of the series, Dungeon Master, Venger, and Tiamat?

No, you don’t. Because no such episode exists. This is the opening shot of the first episode of the Dungeons & Dragons animated series.

The show’s 1 minute intro doesn’t sum up the events of an origin story episode, it replaces the need for one.

Cut To The Chase

Don’t underestimate the effectiveness of powering through an intro. If you’re worried about your players latching onto your adventure hooks, sum up how the PCs got into the current situation then start the session with the adventure underway. It’s important that the actions your say the PCs took in your summary line up with what your players think their character would do, and for the session to start with meaningful choices to avoid accusations of railroading.

Every two weeks, Ryan Costello uses his experience as a Game Master, infused with popular culture references, to share his thoughts on best GMing practices to help his fellow GMs. Often deconstructing conventional wisdom and oft repeated GMing advice, he reminds his fellow GMs that different players play the game in different ways, and for different reasons.