Dustin read the title of the previous installment of Behind The Screens, Dealing With A Marshall PC, and somehow assumed it referred to a Pathfinder option and not Paw Patrol. Weird.

The Pathfinder option in question is the 2e Marshal archetype. Given the archetype’s abundance of offensive and defensive abilities, Dustin assumed the article covered handling overpowered characters. In fact, the article talked about handling underpowered characters. Still, Dustin’s confusion inspired this follow-up article. I resisted the temptation to go with the confusingly similar title Dealing With A Marshal PC.

Diagnosing An Overbearing PC

Before you can deal with an overbearing PC, figure out what about the build flags it as overbearing. Generally, a PC feels overbearing for one of the following reasons:

Too Successful

No matter what challenge you throw at the party, this PC clobbers it. Effectively challenging this PC means overwhelming the rest of the party, but choosing to challenge the rest of the party means this PC dominates the encounter.

Too Useful

Somehow, no matter what the party faces, this PC can contribute. Their niche is the entire game you’re playing. The PC isn’t min-maxed, they’re mean-medianed.

Too Much Spotlight

Maybe the PC isn’t overpowered. Maybe the player is overwhelming. In victory and defeat, the player makes everything about their PC.

What’s A GM To Do?

Let’s get the obvious out of the way:

- Fun. Any obstruction to the fun of someone at the table, us included my fellow GMs, needs to be dealt with.

- Talk to the player. They might not notice the issue, and might be your greatest ally in solving it.

- The operative word is “Too”. Being successful, useful, and in the spotlight are not problems, until they’re too successful, too useful, and too in the spotlight. Being too much of anything is, by definition, reaching a problematic proportion.

With the pillars of GMing advice covered, and whataboutisms shushed, let’s look at addressing these issues.

Relative Heroism

Unlike XP and levels, which we give out evenly across all players at prescribed times, Hero Points are ours to hand out as we please. Grade your heroes on a curve, my fellow GMs.

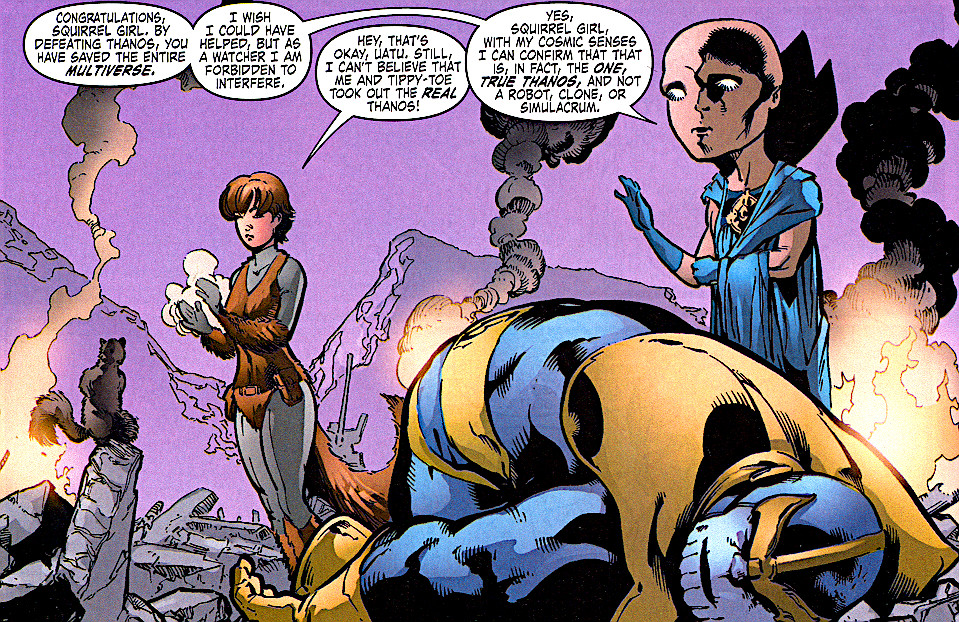

Take the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Across the 26 movies in that series, we’ve seen close to 100 heroes battle villains and save innocents. But which MCU character deserves a Hero Point the most in my eyes?

When the most powerful character in the party faces the toughest opponent, that’s not going above and beyond. It’s characters face actual challenges who deserve to be rewarded. Hero Points reward exceptional behaviour.

The player who gives monologues after every battle, meeting with every quest giver, and ordering every meal at the tavern doesn’t need a cookie every time they open their mouths. But if the mousey player speaks in character for the first time in a month and you appreciate that, toss them a Hero Point.

For a player more influenced by the carrot than the stick, you can setup a Pavlovian system to curb their problematic behaviour. They get a Hero Point for letting another player give the speech. For passing on the Feat that expands their repertoire to cover yet more situations. Yes, people play the game in different ways and for different reasons, but everyone at the table should be having fun. If the way someone plays impacts the fun someone’s having, find other ways to cater to why the problematic player plays that way.

Divide and Conquer

I can’t stress enough the mistake it is to increase the difficulty of the game to cater to the power level of an overpowered character. You’re much better off thinking of the party as two parties: The overbearing PC, and the rest of the party. It’s a different kind of balancing act, because you’ll need to shift the formula of the encounters. We’ll call them the A challenge, for the overbearing PC, and the B challenge, for everyone else.

Not every encounter needs to be split in this way. Every third to fifth adds the variety needed to get the spotlight off the overbearing PC. Plot them like Mario Party 1 vs 3 minigames. Sometimes the 1 player gets the advantage. Sometimes the 1 player is at the mercy of the other 3.

Sometimes the A challenge gets all the attention. The party needs to fight a necromancer and his horde of undead. The overbearing PC takes on the necromancer to stop the influx of undead, the party needs to cull the horde to minimize the damage of unchecked undead.

Sometimes the B challenge is the main event. A corrupted druid in a stone cell calls to the plant life outside, and only the overbearing PC can hold them off. They play a skill challenge mini game against the plants beating down the door while the PCs fight the BBEG druid.

The same works for roleplaying encounters. The silver tongued player is the only one captivating enough to distract the queen’s bodyguard while the rest of the party present evidence to convince her to call off her army.

Channel Your Feelings

Bottling your frustration shakes that soda until you can’t take the cap off without an eruption. Share your feelings. A great way to do so is through story telling. And wouldn’t you know it, roleplaying games tell stories!

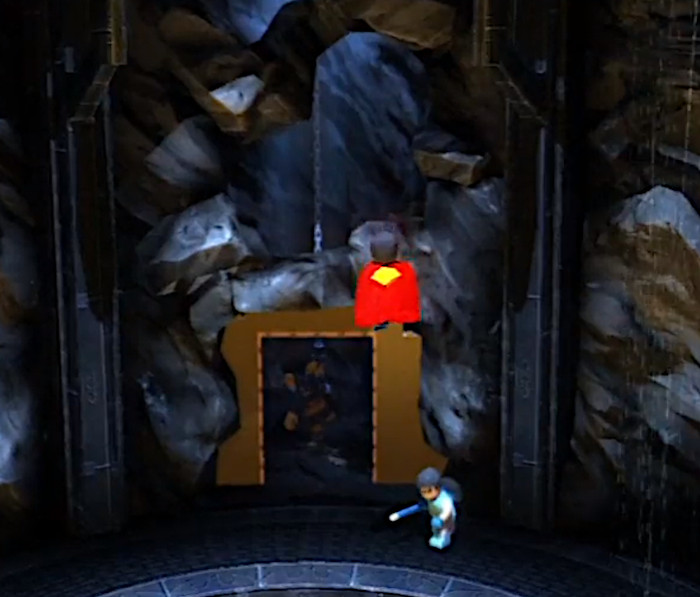

There’s a brilliant sequence in Lego Batman 2: DC Super Heroes that shows the power imbalance between Superman and Batman.

After villains destroy the Batcave, trapping Superman, Batman, and Robin inside, the three heroes must manually ascend a deep pit to reach Wayne Manner. Batman and Robin jump from platform to platform, use their individual gadgets to solve puzzles and unlock new avenues to reach the top. Superman flies. The whole way. I love that the designers didn’t write Superman out in a cut scene. He’s a fully playable character in the level. Occasionally, he uses one of his powers to help Batman and Robin. But mostly, Superman hovers at the top of the screen as a constant reminder of how his powers trivialize Batman’s struggles.

Player actions form puzzle pieces. We put the pieces together and make the picture.

So if one player succeeds in one roll what it takes the other players forever to accomplish over multiple attempts and failures, we have the power to contextualize that however we feel makes the most interesting story. Quickly move on from the player who succeeds, but detail the struggles of the other players, the fearful consequences they narrowly avoid, and their sense of accomplishment when they earn the big victory. Superman may get to the top faster, but Batman’s journey was more interesting.

Every two weeks, Ryan Costello uses his experience as a Game Master, infused with popular culture references, to share his thoughts on best GMing practices to help his fellow GMs. Often deconstructing conventional wisdom and oft repeated GMing advice, he reminds his fellow GMs that different players play the game in different ways, and for different reasons.