Previously I talked about how to police yourself when GMing to maintain a consistent tone. The purpose of that article was how to answer player queries without giving away additional information.

PLAYER: I search X for traps.

GM: X? Oh, OK.

Oh no, some part of the GM brain thinks. I’ve told more that I said! By not anticipating that a player might search X for traps, the GM tells the player that X isn’t trapped, and that X probably isn’t that significant.

And that can be OK.

Self-awareness is important to what we do, GMs, but before you commit to neutralizing your reactions, understand the power of GM inference.

In Behind The Screens, Ryan Costello offers advice, ideas, and insight for the Pathfinder GM. He deconstructs popular GMing advice to account for different styles and motivations of Game Masters and players. Afterall, everyone games in different ways for different reasons.

Framing the Stage

“Theatre of the mind” is the parlance for roleplaying games without an emphasis on maps and miniatures . However, even if your table has an elaborate, Order of the Ambre Die-esq setup, imagination fills in many blanks about the game, and the table has a lot in common with a stage.

Like the audience of a theatre performance, players have a set point of view on the table. Usually straight on, or at an upward or downward angle in theatre, and bird’s eye view at a table.

If a director wants to foreshadow the importance of a prop, they have the set designer set it up somewhere prominent, or have the cast obviously interact with it. Otherwise, all props are created equal and either the audience is forced to process a multitude of items that seem important, or they disregard all items as unimportant. This can be your goal -I saw a murder mystery play with audience interaction where anything on the set could have played a role in the murder, so high alert was the reaction the play wanted from the audience- but is better off avoided if it’s not.

Unlike a director, you are not in control of all the elements on stage. Your audience is also your cast, and if a character interacts with an unimportant prop, it can suddenly seem important to the other players. And a poorly timed low skill check can leave a lingering doubt as to its importance. Heck, a high skill check can be seen as evidence that something is extra important because the truth is super hidden. Basically, all things being equal, there is no difference between a character failing to find anything and a character successfully finding nothing.

The Power of The Unsaid

Theatre uses techniques and tricks to control what the audience focuses on, whereas cinema has cinematography and score to set the tone. I’ve talked before about how I am not a visual person, but I am 10x more visual than I am musical, so you are right to question my qualifications when I say this: Our role as GM is the cinematography and score of our games.

Have you ever watched a horror movie and things just felt off? A character opens a closet door and you gasp, then chuckle to yourself when nothing happens? That’s because there is so much more going on in the scene than what we see.

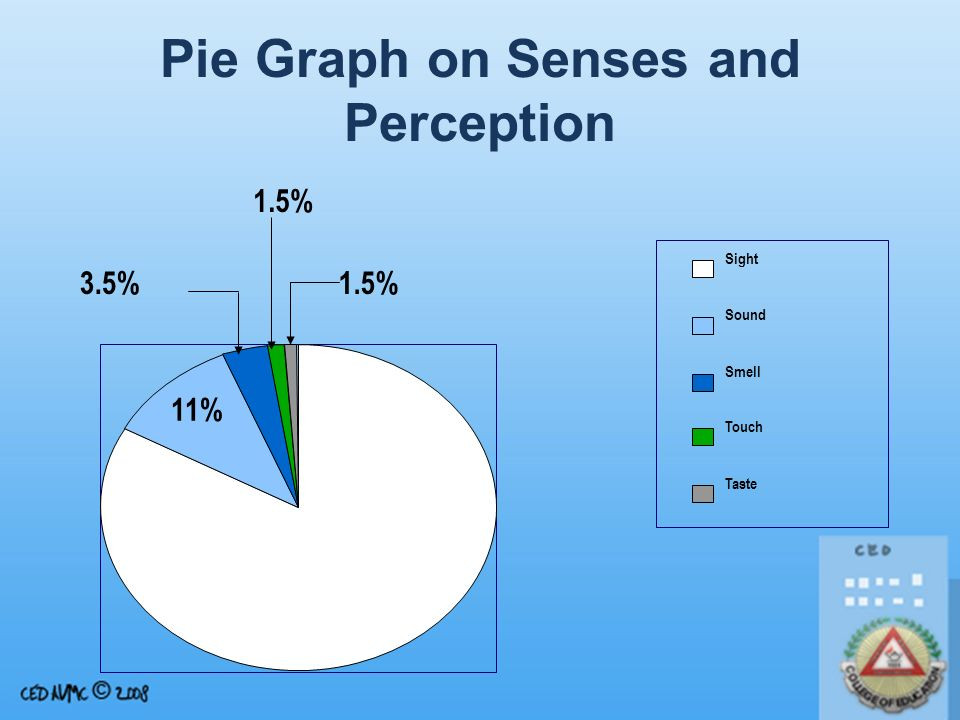

The human senses are not balanced. If we were playing a game where classes were based on the 5 senses, you’d be a fool to play anything other than sight unless you were prepared to lag behind all of the visual characters. If you’re playing taste, you might as well be sight’s familiar.

Furthermore, each sense contains a spectrum of subtle variation, especially (for us humans) sight and sound. Cinematography is the exploitation of the more subtle segments of the spectrums. Doing so plays on our anticipation and subconscious. Done well, a movie becomes more than moving pictures.

You direct the camera with your descriptions, but you direct the tone with your subtext. You can be intentionally subtextual (“Oh, you want to open the door without checking for traps?”) or unintentionally (“Remind me, what’s your marching order?”). These queues represent the subtle sensory input the PCs receive. No one in the world asked the characters what their marching order was, but when we ask for the marching order, it can be seen as the characters’ experience kicking in at the last second that there might be imminent danger.

There are tabletop soundtrack tools, most famously Adventurous sponsor Syrinscape, but they serve a different purpose than a movie’s score. A Syrinscape soundset creates atmosphere, providing the right mood of music and foley appropriate to the setting. Because it and similar programs are generic, we as GMs would have to dedicate a lot of time before and during the session to transition between soundsets in time with the dramatic beats of a scene. This is also not what these programs are designed to do, so a lot of our effort would be square pegging that round hole.

All to engineer a response that GMing creates naturally.

Note: This article covered the passive side of using your GMing tendencies to your advantage. In a previous Behind The Screens, guest blogger Vanessa explored deliberate choices you can make to increase the cinematic feel of your game.

Use Your Voice

This article is not a reversal of a previous position. There is value in knowing your GMing tendencies so that you can control the intentionality of your reactions. But before you see showing your hand as some kind of GMing sin, ask yourself what you and your group gain when you control the subtext of your responses. If players know there is more to your responses than what you say, they have a reason to hang on your every word. Understand when the game benefits from subverting subtext and when subtext adds a layer for players to consider.