You players scrutinize everything you say and do as their GM. If a player says they’re sensing motive on an NPC and you say “oh, sure” instead of just “sure,” that “oh” betrays that there’s no reason to suspect this NPC. You want to avoid the subtle GMing cues you might not know you do to minimize giving away metagame information. But how?

Board game traitor mechanics.

Even though cooperative play was found in some of the earliest video games, it wasn’t a popular mechanic until 2005’s Shadows Over Camelot. Even then, Shadows and other early cooperative games didn’t fully commit to the cooperation, instead introducing a traitor mechanic to make players hesitate about how much they could cooperate with their fellow players when ganging up on the game. This traitor grey zone in mostly-cooperative board games has a lot in common with a GM’s relationship with the players.

Although cooperative play helped set Dungeons & Dragons apart from the miniatures skirmish games from which it evolved, RPGs aren’t cooperative games in the same way as coop video games and board games. In those terms, an RPG like Pathfinder is somewhere between coop and one-vs-many, because the GM acts as the engine that the players are up against. It’s not fully cooperative because the GM controls every obstacle the PCs face, but it’s not a fully competitive relationship, because if the players lose, the GM loses as well and the campaign either ends or is never the same way again.

As the traitor in a cooperative game, your loyalties are also split between the team’s goal and your own. Like a GM, you are working with the loyal players while simultaneously manipulating events to go against them. Being a traitor is more subtle than GMing, of course; if the traitor is too obviously not a team player, you will be outed and usually that makes winning harder or impossible, whereas everyone knows that the GM is the one controlling the baddies. However, playing as a traitor is a great way to get into your own head and learn your tells.

There are distinct experiences playing a cooperative game with a traitor mechanic:

- Playing the game never having been the traitor;

- Playing the game as the traitor for first time;

- Playing the game as not-the-traitor for the first time after having been the traitor.

For experience 1, you play the game without a care in the world. You’re a bit suspicious of everyone, but only a bit since anyone could be the traitor so why dwell on it? You might say and do things with as little subtlety as the rules allow to let everyone know you’re not the traitor.

Experience 2, then, when you are the traitor, every action you want to take is accompanied by the question “how did I do this when I wasn’t a traitor?” You analyze every decision but probably lacked the forward thinking to keep tabs on yourself when you were loyal to the benefit of yourself when you would be the traitor. You will never play the game the same way again.

The next time you play the game as a loyal player, experience 3, is layered with the knowledge that your allies could be your enemies the following game. You catalog your own behavior, and theirs as well, like Batman putting together dossiers on how to defeat each member of the Justice League in case any of them ever goes rogue. You definitely don’t want it to be too obvious that you aren’t the traitor because then it’s that much harder to be the traitor in the future.

Now when you play as a traitor your paranoia and reflection are replaced with cold, calculated wisdom. Everything you do has the double edge of seeming innocent and of advancing your goal.

This is the frame of mind you want to capture as a GM. Whenever you sense that you’ve shown your hand with a subtle or even non-verbal tell, remember it. Squash it. React to every Sense Motive check like the NPC could be the ultimate villain of the campaign but the party will never know. Every inch of every room has equal chance of being trapped if players are to believe your still, neutral eyes.

If you want to practice keeping a straight face while plotting your friends’ demise, here are a few cooperative games with traitor mechanics I’d recommend:

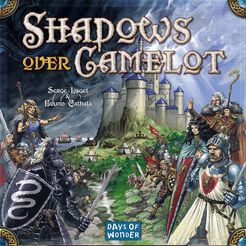

Shadows Over Camelot: This game does the traitor mechanic right in so many ways. First, rules like not being allowed to say specific numbers on cards and forcing everyone to take an evil action the end of their turn help the traitor stay hidden even if they are selfish. Second, a game can have no traitor but the players wouldn’t know. Some players will be paranoid when they don’t need to be and others will see the first sign of loyalty as reason enough to assume everyone is loyal. It gives the traitor psychology to watch for. Third, even though the traitor’s goals are diametrically opposed to the loyal players’ goal, there are enough good actions that advance both goals equally that the traitor player never feels lost for a productive action. Finally, accusing another knight of being a traitor is an action, and being wrong comes with a penalty. A loyal player needs to be confident or they hurt their team.

Shadows Over Camelot: This game does the traitor mechanic right in so many ways. First, rules like not being allowed to say specific numbers on cards and forcing everyone to take an evil action the end of their turn help the traitor stay hidden even if they are selfish. Second, a game can have no traitor but the players wouldn’t know. Some players will be paranoid when they don’t need to be and others will see the first sign of loyalty as reason enough to assume everyone is loyal. It gives the traitor psychology to watch for. Third, even though the traitor’s goals are diametrically opposed to the loyal players’ goal, there are enough good actions that advance both goals equally that the traitor player never feels lost for a productive action. Finally, accusing another knight of being a traitor is an action, and being wrong comes with a penalty. A loyal player needs to be confident or they hurt their team.

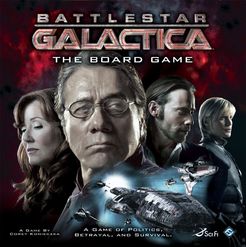

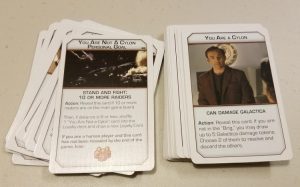

Battlestar Galactica – The Exodus Expansion: The base game of Battlestar Galactica is amazing and tense, with a strong possibility that there is a traitor right from the beginning of the game and a mathematical guarantee that half of the players are traitors starting halfway through the game. That self-consciousness of watching how you take loyal actions in this game

Battlestar Galactica – The Exodus Expansion: The base game of Battlestar Galactica is amazing and tense, with a strong possibility that there is a traitor right from the beginning of the game and a mathematical guarantee that half of the players are traitors starting halfway through the game. That self-consciousness of watching how you take loyal actions in this game  because of how it will affect how you play a future game when you’re a traitor? You have to do that right from the beginning.

because of how it will affect how you play a future game when you’re a traitor? You have to do that right from the beginning.

The Exodus Expansion specifically introduces Conflicted Loyalties. While the humans and Cylons have opposed win conditions, Conflicted Loyalties add secondary win conditions, like the humans have to win but with less than a certain Population. This experience is most like GMing in that you are working with the players up to a point, and working against them in a mix of subtle and overt ways.

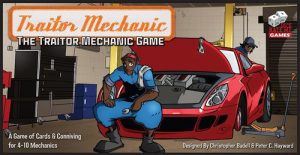

Traitor Mechanic: The Traitor Mechanic Game: Not a joke (well, OK, a bit of a joke), in Traitor Mechanic: The Traitor Mechanic Game, you play as mechanics working together at a garage but one of you is trying to sabotage the business. This game makes the list because the traitor needs to betray early and only needs to successfully betray the group a couple of times to make it hard for the loyal mechanics to win, but it’s very hard to be subtle about a betrayal. It’s the fastest and cheapest cooperative game with a traitor mechanic that I know of.

Traitor Mechanic: The Traitor Mechanic Game: Not a joke (well, OK, a bit of a joke), in Traitor Mechanic: The Traitor Mechanic Game, you play as mechanics working together at a garage but one of you is trying to sabotage the business. This game makes the list because the traitor needs to betray early and only needs to successfully betray the group a couple of times to make it hard for the loyal mechanics to win, but it’s very hard to be subtle about a betrayal. It’s the fastest and cheapest cooperative game with a traitor mechanic that I know of.

GMs do use their player’s scrutiny to our advantage, of course. We’ve all “Are you sure?”ed a player about to do something dangerous or who was 1 shy of hitting a DC. We’re told to occasionally roll dice for no reason other than to keep players guessing. However, that’s a tradeoff for the times players have taken advantage of our little slips in ways that undermined our plans. If you don’t think the trade is worthwhile, you might find total neutrality in all situations more effectively throws players off than deliberate evil. Paranoia comes from when your environment and your gut feelings don’t mesh. Opening that door won’t fill the room with acid or surely the GM would be reacting in some way. Any way. Right?