Continuing the topic suggested by Discord chatter AJ, today we look at the importance of balance between rules in the game.

Mechanical Balance

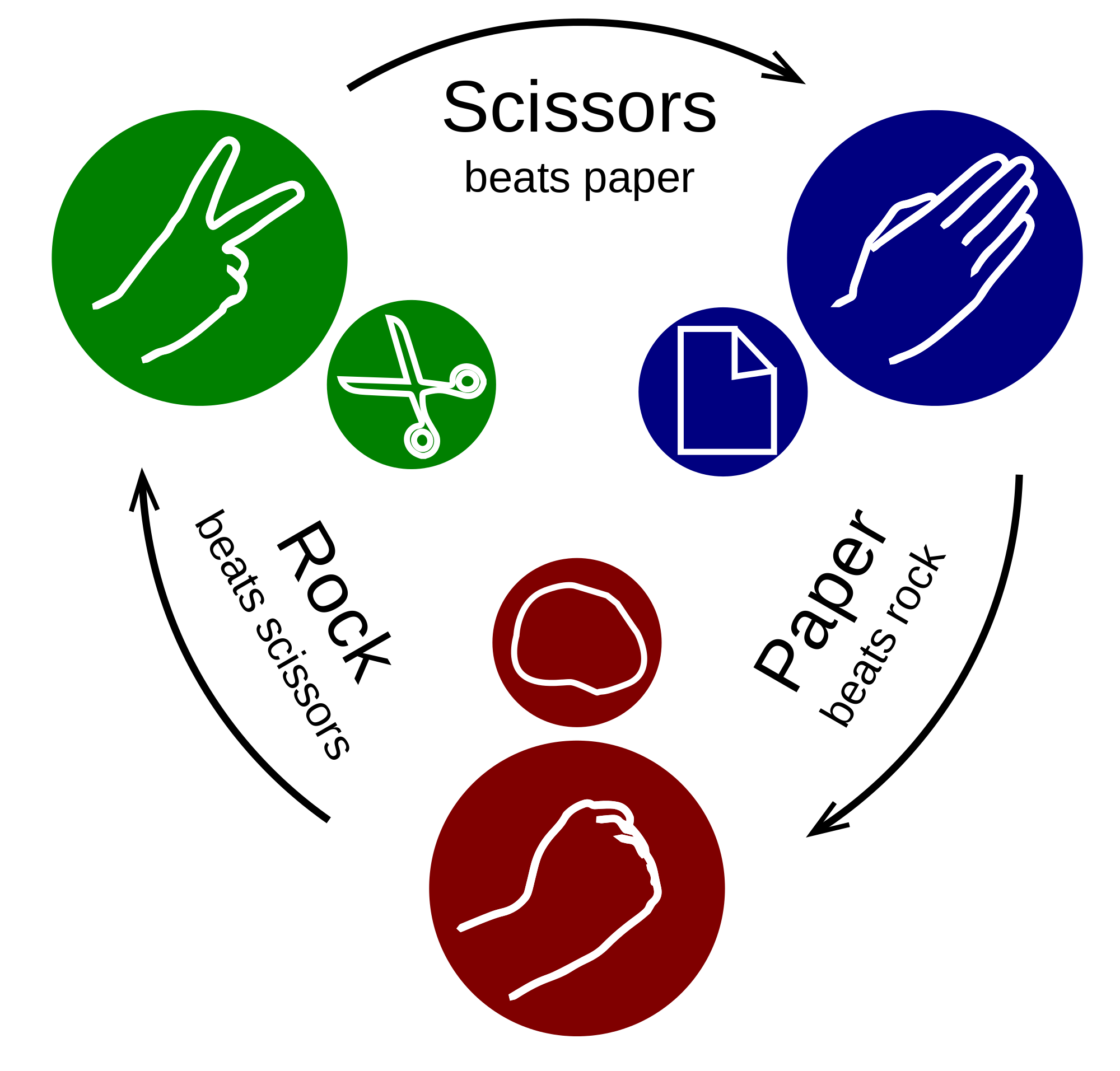

A game is balanced when all options have equal effectiveness. Rock–Paper–Scissors is balanced because every option has an equal number of options it beats, options that beat it, and options it ties with. Whereas where I grew up there was a variant called Rock–Paper–Scissors-Match where a Match (represented by a single finger) beat Paper but lost to Rock and Scissors. This meant that Rock and Paper were mechanically superior to Paper and Match.

If we were game designers and not just kids who messing with a game in ways we didn’t understand, we might have been able to add elements to turn this lack of balance into depth. The simplest way would be to add a points element, turning the variable odds into a feature!

Rock–Paper–Scissors is symmetrically balanced. Like Chess or Checkers, every player has the exact same options. It doesn’t matter that not every piece in Chess has the same capacity to achieve, the sum of the sides is not only equal, it’s the same. Symmetrical options would make for a dull RPG, however.

A good example of an asymmetrical game is Street Fighter. Cloned characters notwithstanding, each character has unique moveset and statistics, like strength, speed, and reach. The designers ascribed values to every adjustable element of a character and aimed to design each character to meet a certain value. In a controlled environment, any two characters should have equal opportunity to win the match.

What is the point of a game where all options are differently equal?

Accessibility Balance

The goal of asymmetry in your game is to add variety. In a board game or video game, asymmetry adds replayability. If you like a game but find play repetitive, changing who you play changes how you experience the game.

In a roleplaying game, asymmetry is essential to the play experience. If playing a wizard doesn’t feel different from playing a fighter, the difference is superficial. One of the reasons I think the kineticist is such a successful design is because it feels like a wizard that plays like a fighter, but in a way that fills a niche instead of feeling like the concept and mechanics clash. If a player tries a wizard and finds spell casting frustrating but doesn’t want to play a fighter because they look boring, the kineticist is the next class I would suggest.

Accessibility balance is different from mechanical balance. You aren’t trying to make sure any two items on opposite ends of a scale have the same weight. You are trying to balance the needs of the player base.

It’s why I shake my head when I see arguments that certain options should be better or removed from the game because there are mathematically better options. The mathematically better options are typically more complex. Accessibility balance means the game needs some more and some less complex options. There’s no point having complex options if the less complex options are mechanically superior. The wizard might be optimally better than the sorcerer, but that doesn’t mean the sorcerer shouldn’t exist. The sorcerer gives a similar but simpler experience as the wizard, which is why it needs to exist.

Going back to the simple options being weaker by necessity, Mark Brown recently released a video about synergy between options. He talked about how when he found a combination that was greater than the sum of its parts, it increased his enjoyment of a game.

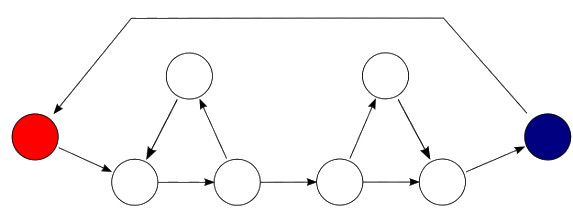

For builds to matter, there needs to the potential to unlock more powerful options. This is important for the engagement of many players. For some options to be more powerful, or have the potential to be more powerful, there need to be comparatively less powerful options. Otherwise the complexity of a build doesn’t matter.

One of the areas Pathfinder fails at this is in prerequisites for options. Often prerequisites represent the worst overlap of complexity and power, requiring forethought that players who want a simple build don’t enjoy, and commitment to suboptimal options that players who prefer more complex builds don’t want. If simple building is a pleasant path through the forest and complex building is brachiating through the treetops, options with two many prerequisites are invisible walls that the only way to get over is with a running start.

In Conclusion

Mechanical balance can not come at the expense of accessibility balance. One of the strengths of Pathfinder 1st edition is that it balances power with complexity, one of the most important balances for a roleplaying game to achieve.