Hello, lovely readers! I was originally planning to write a new Iconic Design today using some of Luis and Eleanor’s awesome new archetypes, but I ended up getting into a big Twitter discussion with some random people on a topic that’s very near and dear to my heart, and since its a topic that’s applicable to Roleplaying Games I wanted to bring it here. That topic is redemption, specifically as it pertains as a story element.

As you can imagine, with a topic like redemption on the menu it’s clear that we’re going to be serving up some big philosophical quandaries here at Guidance, so strap yourselves in and let’s get started!

What Is Redemption?

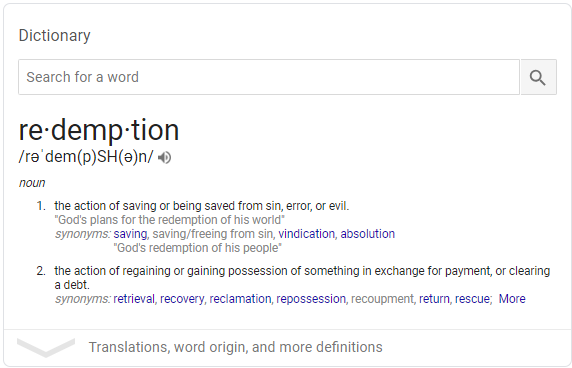

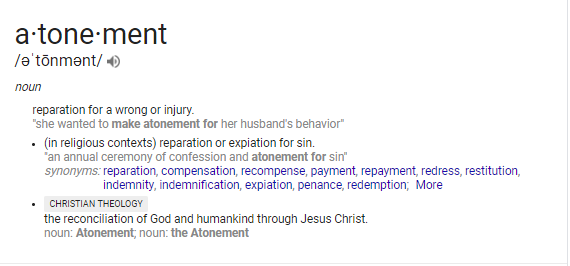

Before we begin, I think it’s helpful to actually stop and define what redemption is. If you Google the word “redemption”, this is what you’ll find:

So when we talk about redemption, we’re talking about saving someone or something from wrongdoing, mistakes they’ve made, or evil in general. But when we’re talking about saving someone, we don’t necessarily mean like rescuing a dude in distress from a dragon. That’s definitely a rescue from something evil, but redemption has a strong connotation of, “saving one from one’s self”. The second definition actually reinforces this; when you look at the second definition and you see we’re talking about regaining possession of something or clearing a debt; in this case, you’re regaining possession of your goodly virtue.

So when we talk about redemption, we’re talking about saving someone from their own mistakes, sins, or evil actions.

“Earning” Your Redemption

To summarize a very long paragraph that I wrote and later cut because it was KILLING the flow of this article, many individuals get upset when redemption comes too easy to characters in a story. It’s a commonly held belief that redemption is something that has to be earned by a character, usually through a long process that involves gaining others’ trust and proving they’re deserving of that trust. The golden standard of this idea is, without a doubt, the character of Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender. If you’ve never seen Avatar: The Last Airbender, first things first GO OUT AND CONSUME THAT CONTENT. Seriously, Avatar: The Last Airbender has its flaws but it is by and large one of the most influential piece of American animation to be released in the last decade and it probably end up being a major “cultural icon” in the way that Star Wars is. Seriously, go watch it.

Zuko spends the first two-thirds of Avatar: The Last Airbender as the series’ primary antagonist, though the show goes to great lengths to flesh Zuko out and make him an interesting character that the audience really ends up becoming attached to. This changes in Episode 21, the first of Season 2, when Zuko is basically forced to stand down to a new antagonist, resulting in he and his uncle going into hiding. This is where we start getting hints that Zuko might not be a terrible person behind his previously single-minded role as the series’ antagonist, but at the umpteenth hour when Zuko has a chance to make the right choice he blows it and reaffirms himself as an antagonist at the end of the second season of the show. It isn’t until Season 3, at Episode 53 and a whopping 32 episodes after the series starts exploring Zuko as a character, that his redemption is “complete” in the sense that he’s allowed to join the main cast as a hero. Yet even after this episode, there are two ADDITIONAL episodes whose sole purpose is to allow Zuko to win over two specific members of the main cast, so really it takes about 34 episodes for this character to be redeemed.

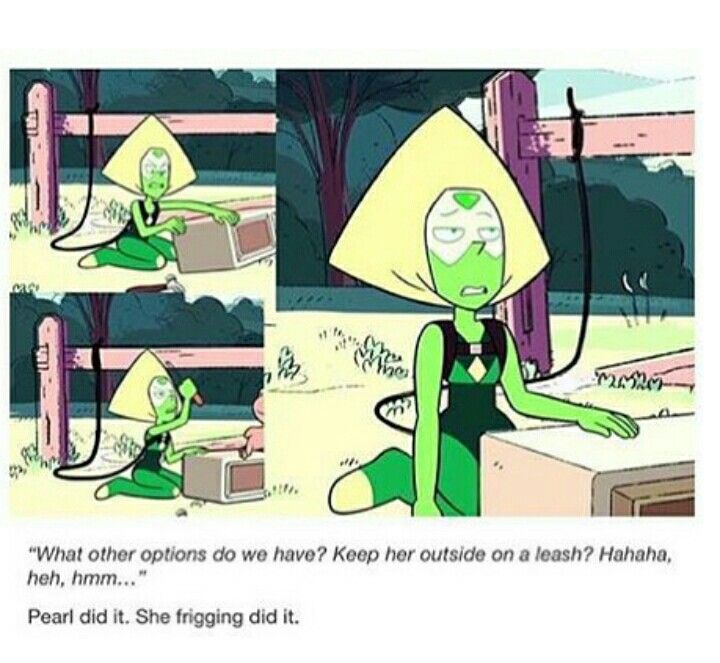

If 17 hours of television makes a “justifiably earned” redemption, its no wonder that many other redemption arcs seem too quick to some fans. To provide an interesting contest, Steven Universe, another one of this decade’s powerhouse animated features that is going to be influencing the medium for decades to come, is notorious for its relatively quick redemption arcs. A typical episode of Steven Universe is about 15 minutes long, and it isn’t uncommon for villains to get their redemption in the final moments of one of these lightning-fast episodes. For many critics of the series, this is too fast. But I’d like to make the argument that it ISN’T too fast because we as fans don’t really understand redemption. Here’s why.

What Makes a Redemption?

So when we’re talking about a redemption, what’s the most important part? If we look at Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender, we can identify several key character moments where Zuko’s worldview begins to change rapidly, and ultimately his changed worldview leads to his redemption. As much as good and evil are cosmic forces in a game like Pathfinder, redemption for us mortals is more a change in behavior reflective in a person who engaged in behaviors that we did not like suddenly engaging in behavior that we now like, and doing so with enough consistency that we trust and respect the individual for having changed. With this in mind, let’s examine a number of “important moments” in Zuko’s adventure that caused him to change his worldview to align with those of the primary cast.

- When Zuko is being hunted by the Fire Nation, ruled by his father, he encounters a young healer who opens his eyes to what war does to a population. He’s been fed Fire Nation propaganda all his life, and now he has real, tangible proof that the ideas he’s been led to believe are wrong.

- Zuko teams up with the Avatar and his friends to fight an enemy. That exchange doesn’t end well for Zuko, but it lays the groundwork for his redemption.

- Zuko encounters one of the Avatar’s animal companions and decides to free them from captivity without any promise of thanks or compensation. This decision fills Zuko with so much conflict that he passes out ill from it.

- Zuko betrays the Avatar and almost kills him, hiring an assassin soon after to try and finish the job. Furthermore, Zukosacrifices a loved one in order to regain his lost status within his homeland. At this point, it seems like Zuko’s redemption has collapsed.

- On an “anime beach episode”, Zuko reveals that he doesn’t know right from wrong anymore and it infuriates him. It’s a huge, emotional scene that confirms to the audience that Zuko’s old character development wasn’t gone. Later he rejoins his father as his right-hand man, but realizes that it feels wrong and he is only perfect to his father if he isn’t himself.

- In the very next arc, Zuko renounces his father and decides to join the protagonists, defying him outright and escaping in true dramatic fashion.

As you can see, Zuko’s redemption arc has a lot of small points that slowly show the character changing. But do all redemption need to be this involved? The simple answer should be “No”, but many people expect them to be anyway. Ultimately, redemption represents a dramatic shift in worldview, usually from one deemed “evil” to one deemed “good”, to the extent that the change is actionable for the redeemed character. As soon as the character takes a high-stakes action with a different worldview, they are essentially redeemed. Let’s look at this in deeper detail.

- Redemption must be actionable. It isn’t enough to simply say, “I’ve changed my ways”. You need to do something to prove it.

- Redemption, like righteousness, demands sacrifice. A character isn’t really redeemed until they take an action that requires them to sacrifice something. For Zuko, his redemption occurs at the moment he defies his father, sacrificing the royal lifestyle he wanted so badly to reobtain. In Steven Universe, Peridot’s redemption happens the moment she mouths off to her superior and defies her orders, thus labeling her an enemy of her home world. But do redemptions need to be so dramatic in scope? Not necessarily. Simply admitting one was wrong and asking for a chance at forgiveness can likewise be the action needed for a redemption, because at that point you’re sacrifice is the notion that what you did was acceptable. The acceptance of true guilt can be a form of redemption if that guilt is acted upon in a way that changes their outlook and future actions.

- Redemption needs to be acknowledged and accepted in the eyes of the redeemer. Yes, this one sounds weird, but let me try to explain. A character is only redeemed in the eyes of individuals, not universally. In the case of Zuko, the moment he became redeemed in the eyes of the audience he became vilified by his father. Redemption isn’t universal, even in stories, and as a result one is only redeemed in the eyes of an individual if said individual recognizes the actions and sacrifices taken towards redemption. No matter what you do, you are only redeemed if those you are seeking redemption from view you in such a light. (Hence why Avatar: The Last Airbender gives us a hilarious scene of Zuko practicing his apology speech to a frog.)

This brings up one of the most important aspects of redemption—we as audience members only get to decide what constitutes a satisfying redemption in OUR eyes, we don’t get to decide that from the eyes of other characters or people. Let me explain further.

A Faster Redemption

So now in order to finish the topic of redemption, we need to turn to animation’s ultimate redeemer, Steven Universe of the TV show with the same name. Steven Universe’s creator, Rebecca Sugar, has said that Steven Universe, “Has no villains,” and in many ways that’s true. No one’s really evil so much as they’re operating on broken logic from places of fear or personal suffering. This is one of the reasons why so many villains in the show get redemption arcs, though they’re arcs that many fans aren’t particularly satisfied with because they happen so quickly. I would like to posit, however, that the fast-paced redemption of the show is less of a flaw and more a result of character development. Let me explain why.

- In Steven Universe, the character Peridot is literally the first recurring antagonist that the series ever had. Before her, it followed a monster-of-the-week format exclusively that Steven and the Crystal Gems always defeated. When the Crystal Gems finally defeated Peridot, however, her final words before “poofing” (thing of her gem as a super computer and poofing as the process by which that computer is turned off temporarily due to damage to her artificial body) worried Steven, so he rebooted her anyway and tried to work what she knew out of her, eventually winning over her trust. Peridot’s knowledge made it clear that the Crystal Gems needed to drill down to the center of the Earth to save it, so they recruited Peridot to help them. These early episodes were VERY terse, with the Crystal Gems and Peridot feuding constantly.

- As the arch continued, Peridot became more helpful as she learned more about the Crystal Gems and their way of life.

- Eventually, Peridot gains an opportunity to radio to her boss, to whom she is very loyal to and is actively opposed to the Crystal Gems. Steven and the Gems try to stop her for fear that the boss will basically destroy the planet, but Peridot puts her job before her new friends and contacts her boss anyway. The Gems can’t risk being seen by Boss Lady, so they basically can’t interfere with the space phone call.

- Peridot ends up defying her boss to the extent that her boss tries to have her killed. Twice. This solidifies her allegiance to Steven and his friends.

Now, I’m sure you can see some similar progression here, but one important thing to note is that the start of this arc and the end of this arc are only eight 15-minute episodes apart, or four hours. MUCH faster than Avatar: The Last Airbender. And in terms of screen time, this isn’t even the fastest of the redemptions. Three characters get redeemed after roughly 3 minutes of real effort in Steven Universe’s season finale, and that’s okay.

Why?

Because Steven Universe is a completely different character from Katara, Sokka, Toph, and Aang.

Steven Universe, the Ultimate Redeemer

One of the most important character traits of Steven Universe is his optimistic outlook. Steven always sees the best in others and is always willing to give them a chance to be better people. In the aforementioned Peridot redemption arc, we see Steven accept Peridot for who she is and the help she can provide less then five minutes after he and the Crystal Gems have defeated her. He’s always looking for the best in others and giving them opportunities to be better. In a sense, Steven actively tries to help people be redeemed. In fact, Peridot’s whole redemption arc was about HER making the decision to help Steven and become a crystal gem and the Crystal Gems coming to accept Peridot’s redemption. Peridot, Garnet, and Amythest (the Crystal Gems) all treat Peridot like garbage throughout her redemption arc up until the point that she tells off her boss. All three of them question Steven’s decision to trust her throughout her arc. They’re the first to basically say, “I told you so” when it looks like Peridot might betray them. And yet Steven’s faith in Peridot ends up being well-placed when she defects and joins them. This is what establishes Steven Universe as an ultimate “redeemer” character and allows him to redeem others faster as the plot progresses. Steven’s intuition about Peridot ends up being right, so more and more the Crystal Gems trust him in his calls. They respect his pacifism and his ability to see the best in everyone, and ultimately come to trust him.

To put another way, redemption arcs are faster in Steven Universe because unlike Avatar: The Last Airbender, Steven doesn’t need proof from others that they’ve turned a new leaf. He doesn’t need to go on a special adventure with Peridot the way that Katara needed to go on one with Zuko. And it proves the most important facet of redemption stories: the difficulty in redeeming someone is determined by the judgment of the redeemer.

Tying this Back to Roleplaying Games

After reading all these examples and stories, I hope that the one big idea that you take away from this article is that there’s no right or wrong way to redeem a character in your stories. Ultimately your redemption needs to be sufficient for the characters (or players) whose eyes that you want to be redeemed in. Some people are less trusting and need mountains of proof. Some people are more trusting and don’t need any. Sometimes a simple change of heart via the power of friendship is enough, and sometimes real sacrifice is needed to earn redemption.

As a final thought, worth mentioning that redemption is not atonement. Here’s a slick definition for you:

Atonement is reparation, it’s taking something bad that you did and doing what’s needed to make it right. In Zuko’s example, he earns his redemption from Aang and the others about halfway through Season 3 of Avatar: The Last Airbender but he doesn’t truly atone even by the end of the story. He pledges to devote the Fire Nation to helping repair the world, and that story is the start of his atonement. He has a lot of work to do in order to make up for the wrongs he did, after all.

Basically, redemption is being saved from wrongdoings while atonement is fixing the wrongdoings you’ve done. You can’t atone if you haven’t redeemed yourself and vice versa. So the next time you experience a redemption story, don’t look for the main character to have fixed everything as a prerequisite for redemption because redemption is merely the first step towards atonement and nothing more.

Alexander “Alex” Augunas has been playing roleplaying games since 2007, which isn’t nearly as long as 90% of his colleagues. Alexander is an active freelancer for the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game and is best known as the author of the Pact Magic Unbound series by Radiance House. Alex is the owner of Everyman Gaming, LLC and is often stylized as the Everyman Gamer in honor of Guidance’s original home. Alex also cohosts the Private Sanctuary Podcast, along with fellow blogger Anthony Li, and you can follow their exploits on Facebook in the 3.5 Private Sanctuary Group, or on Alex’s Twitter, @AlJAug.