Longtime listener Joker wrote a response to Ryan’s recent Behind The Screens article, A Balanced Game.

Hey Ryan (and readers!) I was inspired by your recent blog to write a response, not to dispute or even argue against your case, but mostly because I wanted to add my personal balancing methods to the pile. I think it’s particularly interesting because as a GM, I have figured out the key to balancing (in my specific case) is not balancing very much at all.

Throwing CR Out The Window

Fairly early on I’ve learned to stop trusting CR (Challenge Rating.) I get the idea behind CR but it simply stops working when you add in a bunch of variables. And Pathfinder is full of variables. Party size, enemy group size, mixing CR values, situational abilities, terrain… There’s so much that adjusts the difficulty of an encounter that using CR is unreliable at best. CR is great for seeing at a moment’s notice approximately how strong a monster is however, so that is it’s only purpose, for me personally.

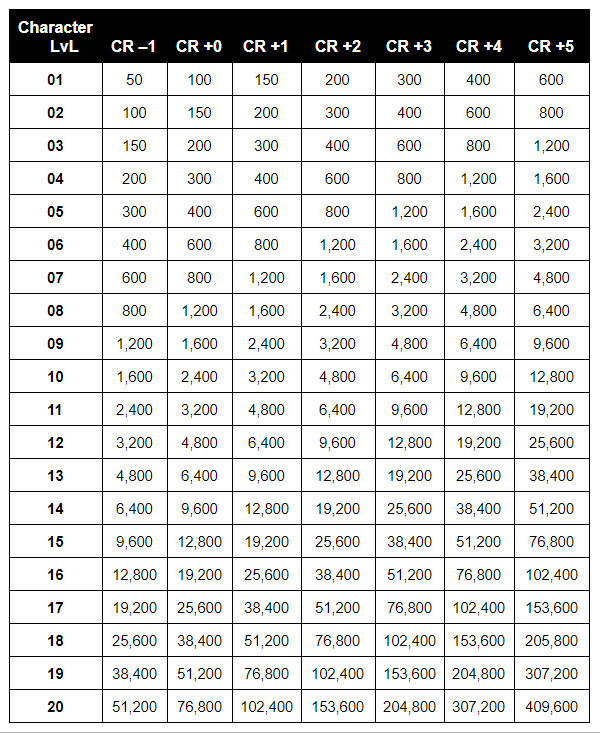

I have replaced CR with EXP-budgeting. For which I use this table:

Source: GM’s Guide to Creating Challenging Encounters. By Alex Augunas

To read this table, simply add your players (say 4 level 3 characters) and select how challenging you want an encounter to be (let’s go with CR +0, aka dead average.) This gives us 4*200 = 800 experience. This is my only guideline, I will aim to add monsters to an encounter that total about 800 experience points in rewards. In addition, I will endeavour to spend about half this budget on one or two larger (budget) foes, and the rest on smaller ‘goons.’ This is the first step in my ‘balancing’ process. And its purpose is mostly to ensure I won’t throw encounters at the party that they can’t handle by virtue of being underleveled for it. That’s the only factor this method accounts for however, level and expected challenge.

Go With What Makes Sense

And here it is I think a lot of people differ. A lot of GMs I know will now start looking for monsters that target a specific save, or that have a strong save themselves (for example, a high will save against that pesky witch in the player party who keeps slumbering everyone and their cohort’s mother!) On the flipside, there’s a common design trope I hear recently where GM’s believe they shouldn’t design encounters that the players aren’t likely to win. They’ll choose monsters or things that have specific weaknesses that cater to the party. Or they’ll remove creatures or abilities from an encounter the party is unable to deal with. While I believe you certainly shouldn’t endeavour to kill the party, there’s nothing wrong with designing something the party is ill-prepared for.

The way I do it, is I look at the circumstances of the encounter. Where is it? Who is present? What would they do in day to day life, and how will their experience and abilities reflect that? If it involves monsters, I choose monsters that are both thematic and cool for the area and feel I’m trying to create. I’ll often even write a short, 1-2 paragraph story as to why this monster is there at that time! Verisimilitude is very important to me personally, and making encounters that above everything else make sense is an integral part of my style.

An added benefit to this method is that I stopped concerning myself with who’s in the party. I don’t think about their saves, their spells or their party composition. Does this mean there’s occasionally a monster there that the party is horribly unprepared for? Like a Quickling when the party has no cold iron weapons. Or something that the party will breeze through? Like a few Ogres against the aforementioned Witch? Yes, it very much does. But that’s the beauty of balancing encounters with this method.

After all of this is done, I ask myself one simple question: Is this encounter aware of the party? And if they are, I will adjust it accordingly. I will do small tweaks to inventories or abilities that the people and things in the encounter would reasonably change to be better prepared for the inevitable encounter with the party. A vulnerable necromancer might invest in a potion of blur to throw off the party’s Rogue. A dragon might search his vault for a scroll of resist energy to ward off the party’s ice-mage who’s got two red-dragon kills to her name already.

How This Affects Play

This has created a few interesting dynamics in my games. First of all, this enables people to play the game how they want to play. Optimizers and math-minded people will find themselves delighted in the fact their optimization works well against the brunt of situations. People who love planning and preparing find themselves enjoying the fact the curveballs the world throws at them are no match for their bag of holding and the various trinkets, scrolls and potions they have collected.

And occasionally… Occasionally the party will lament not investing in that scroll of glitterdust the overeager salesman was trying to shove down their throat. If only they had listened to his far too long and suspiciously impassioned speech. Occasionally they’ll be forced to adapt and overcome, or even to run. But using this method, not once will the players feel crossed or screwed. You didn’t put those monsters there to mess with the party, they’re there because that’s their place in the world. Everything thus far has made sense and when they break this down, this encounter too will make sense. Yes, obviously the cursed monastery has kung-fu zombies in it! Evil was dripping off that place, and everyone in the tavern was talking about the things that go arughghh-HIYA in the night. I bet if we go in there with a few scrolls of cure moderate wounds and a few blunt weapons that fight will go very differently!

This also means you won’t need to pull shenanigans, like upping HP or AC or slapping an advanced template on every encounter.

Conclusion

If you run into balancing issues at this point, it probably stems from one of two things. One of the players is severely over-optimized to the point of trivializing so many encounters your other players can’t enjoy them. Or conversely, someone is so under-optimized they’re constantly at the risk of dying, or worse, putting the party at risk. Both of these scenarios are social issues however, not balancing issues.

I think using the game mechanics to punish or uplift these players is a mistake. One of the elements that makes a game like Dark Souls such a good RPG is that the laws of the world are always the same. They do not compromise and are always the same for everyone. Even the bad guys! If they fall off the map they’re just as dead as you, no matter how huge their boss-name is.

Your best bet is communicating with your players what kind of game you like to run, while they’re most welcome, their playstyle might be better suited for a game revolving around a world that’s designed to kill you, or that’s designed to be explored relatively harmlessly. Rather than a world that’s designed to be that, a living, breathing, realistic world.