The motivation behind my mantra, that everyone games in different ways for different reasons, is rooted in my belief that to fulfill my role as fun facilitator, I must first understand why my players play the way they do. However, after playing with a variation of the same group for 10 someodd years, there was one behavior I never understood: Why are my players always jerks to the NPCs?

Bad Starting Attitude

Across editions, the attitudes of NPCs towards the PCs are, from most hostile to most helpful: Hostile, Unfriendly, Indifferent, Friendly, Helpful. Based on how these attitudes are defined in the Pathfinder 2e Diplomacy skill description, my PC’s starting attitude towards my NPCs was just shy of Hostile:

Actively works against you—and might attack you just because of their dislike.

If there was a guard stationed outside a city who had the gall to ask the party what their business was in the town he was hired to protect, they would flex their character sheets and mock the idea that this lowly warrior thought he could do anything to stop the party if they tried. If a city official brought up matters like the consequences of combat within city walls, the PCs would strawman that official with offers to let the monsters run wild. And if their blatant dismissive attitudes towards every NPC resulted in my NPCs not wanting to give the PCs the help they needed, those same players would lament how “every NPC we meet is a jerk.”

It’s been a few years since I played with that group, and even longer since I GMed them, so the timing of this revelation doesn’t help much, but around New Years an idea struck me that finally shed some light on why they would always make jokes at the expense of every NPC they met:

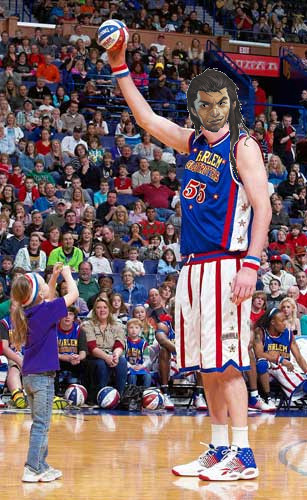

The players saw their characters as The Harlem Globetrotters in a world of Washington Generals.

Dunking On The Helpless

In case this needs explaining, the Harlem Globetrotters are to basketball what the WWE is to greco roman wrestling. The results are predetermined, there are rules but they can be ignored in the name of entertainment, and the players are equal part actors and athletes.

Unlike pro wrestling, there is no backstory or continuity to the Harlem Globetrotters. Every game is an exhibition between the Globetrotters and the Washington Generals, wherein the Globetrotters so outmatch their opponents that they can perform multiple comedy sketches mid-game without the scores ever getting close.

The Harlem Globetrotters defy storytelling conventions. The Globetrotters are so far from the underdog, they are like Goliaths playing a team of Davids, but the Goliaths have the slingshots. Of the two, they are the team more likely to cheat. And while the Harlem Globetrotters as an organization does a lot of charity work, it’s not part of the storyline of the game. They aren’t in the moral right or portrayed as the virtuous of the two. They are the better of the two teams winning a one-sided game and making fun of the less talented teams while they do it.

Pathtrotters

If hindsight allowed for hindtravel, how would I apply this metaphor to improve my role as fun facilitator?

Exciting vs Bland

How are the Globetrotters the protagonists if they are neither heroic nor good guys? It’s because the Globetrotters are different. Their uniforms are flashy, and every player is allowed to customize their look. They have wacky nicknames, sometimes the only name they go by. Occasionally they display superhuman abilities. And by occasionally, I mean 1/game.

The Washington Generals, on the other hand, are generic by design. The few who stand out are drafted to the Globetrotters for being too special. These are like the NPCs we have time to explain, or who elevate above the status of exposition or setting dressing. If we took the time to give every NPC the level of detail of a PC, most of what we do as GMs would be describing the population of the world.

Players As Audience

A lot of the appeal of roleplaying is that players and us GMs are as much active participants as we are passive. We don’t know what anyone else’s turn will yield. In games as dependent on math and probably as Paizo’s RPGs, we don’t even know what our turns will yield! The more we set up a monster as a this terrifying threat, the harder it falls if our d20s don’t feel like rolling double digits.

As a result, players awaiting their turns are left to watch how things unfold. And like someone who bought tickets for a Harlem Globetrotters game, they go in biased in favour of one side, and they’re looking forward to seeing the wacky antics of the side they’re there to see. In fact, a Harlem Globetrotters game might be the only “sporting” event where everyone in attendance is rooting for the same side.

Let Them Dunk

Perram has asked before how many combats should the party be expected to win, and his view is that any estimate that isn’t with 5% of all of them is overestimating how often PCs lose.

Even if Pathfinder rules are mostly combat, the game is not a tactical simulator. If it was, one monster of the party’s average level wouldn’t be considered a threat to the party that outnumbers it four or five to one. The game is designed to put the characters in dozens or hundreds of life-threatening situations every campaign, with the odds heavily in favour of the PCs surviving. Encounters that are less than a moderate threat are more about the opportunity to show off what the PCs can do.

That’s encounters. The group I played with tended to extend this attitude outside of combat as well. They liked making clever remarks and cutting insults, and since the villains don’t survive long to get it out of their systems, so many random NPCs got burned for being there when the party was itching to be clever.

Now, I’ve said before that even if one of our roles as GMs is fun facilitator, that includes our own fun. I enjoy jumping between NPC’s with varying outlook and motivation, seeing what relationships with the party organically form. What Crystal does GMing Adventurous? That’s my GMing goal. So spending years of sessions where the organic result of introducing a new NPC was “that NPC gets insulted and discarded” took away from my fun. However, that doesn’t mean there was nothing I could do.

I remember one storyline that was supposed to be a former villain named Gratt, a telekinetic rogue, attempting to redeem himself by helping the party against his former evil faction, the Six Fingered Gauntlet. The party rejected him, but didn’t kill him, and any time he showed up they aggressively mocked him.

This was perfect. It is not the direction I expected the storyline to go, but it matched the PCs’ motivations, their existing relationship with Gratt, and the world they lived in. Even though it was similar to how they treated most NPCs, it was organic and contextual and therefore satisfying to me.

Knowing that the PCs were just looking for a chance to spin the ball on their fingers and play keep-away, regardless of who, I could have fed them more NPCs who deserved it, hopefully leading to a good time had by all at the table and addressing this behaviour and the need behind it.

Every two weeks, Ryan Costello uses his experience as a Game Master, infused with popular culture references, to share his thoughts on best GMing practices to help his fellow GMs. Often deconstructing conventional wisdom and oft repeated GMing advice, he reminds his fellow GMs that different players play the game in different ways, and for different reasons.